The Atlanta City Council voted March 20, 2023 to put into place rigorous restrictions on new development in the Tuxedo Park neighborhood, capping a multi-decade effort by some to preserve the area’s “park-like” character. The City Council approved the creation of a Special Interest District (SPI-25) with its vote following a recommendation of approval for the regulations by the Atlanta Zoning Review Board (ZRB) and NPU-A earlier this month, and the City’s Historic Preservation Office deeming Tuxedo Park a historic neighborhood in 2020.

The SPI mandates that new subdivisions or developments within Tuxedo Park will follow the area’s “historic pattern” on lots and house placement, specifically, maintaining existing patterns of “long, rectangular lots with straight side lot lines” and “deep setbacks.” The regulations prohibit new subdivisions from creating new public streets, impose lot width restrictions, mandate that all new lots conform to the range of lot depths by other properties on the same side of the street, and that no new lots will be created “unless it contains a depth that is at least twice the length of its width.” The SPI also establishes setback requirements, most notably that all new lots include a front yard setback equal to “one-half of the lot depth,” effectively limiting improvements or construction to the back half of the lot.

The rezoning was spearheaded by Atlanta City Councilwoman Mary Norwood, who said at the March 9 ZRB meeting the legislation provides important protection for Tuxedo Park’s “park-like” character. The passage of this legislation has the potential to affect all Atlantans, if the idea of rezoning neighborhood-by-neighborhood takes hold.

“The most important characteristic in this neighborhood are the deep lots and thoughtful placement of residences,” Norwood told the ZRB.

Tuxedo Park’s historic nature dates to its informal creation in the early 1900s as a neighborhood for wealthy Atlantans in which homes were first built along West Paces Ferry Road, usually summer or country estates that featured residences built far back from the street — a theme the SPI aims to continue. The neighborhood continues to be one of the wealthiest and most desirable in Buckhead. The Tuxedo Park Civic Association, which spoke in favor of the SPI at the March 9 ZRB meeting, wasfounded to “protect the character, integrity, quality of life, and security” of the neighborhood.

Tuxedo Park was considered for historical designation in 1990, but that effort never came to fruition. As such, Tuxedo Park’s century-long history has recently included plenty of jousting over future development of the area between developers and neighbors.

In 2018, the “Pink Palace” property on West Paces Ferry Road was subdivided into three lots, which spurred many members of the neighborhood to begin fighting against what they considered to be undesirable development of the area. In 2020, the opponents of redevelopment celebrated a win when Tuxedo Park earned “historic neighborhood” status through the City of Atlanta Office of Design’s Historic Preservation Studio. That designation quelled an attempt to subdivide a 3.4-acre property on Tuxedo Road, which had been staunchly opposed by Norwood and an organized group of neighbors.

Most recently, a request by Benecki Homes to subdivide a 2.7-acre property along Tuxedo Road and Woodhaven Road— which included an existing home — for the development of two homes caused ire among neighbors. Community members voted 58-1 to oppose the plan during an NPU meeting. But because the proposal complied with local zoning requirements, it appeared primed for eventual approval. The fight was not over, however, as neighbors appealed to the Historic Preservation Studio, which determined in January the subdivision was to be rejected because the proposed lots would not be “long” enough to conform with the area’s traditional design and layout.

The close calls for neighbors opposed to redevelopment of Tuxedo Park spurred the creation of the rezoning. With its passage, hard lines are now set on new development in the neighborhood, and the stringent regulations will thus make it far more difficult to subdivide properties or redevelop lots.

“SPI-25 specifies that new subdivisions will follow the neighborhood’s historic pattern of lot plating and house placement; thus, codifying the City’s Historic Preservation Office’s 2020 determination of this neighborhood as an historic neighborhood,” a City Council press release stated.

While future redevelopment proposals within Tuxedo Park are likely given its history and standing among Atlanta neighborhoods, neighbors now have the backing of the SPI to maintain the area’s character.

“I am so pleased to have the unanimous support of my Council colleagues and the City’s administration for this important legislation,” Norwood said.

THE CITY COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF ATLANTA, GEORGIA, HEREBY ORDAINS, as follows:

Section 1: That the Atlanta Zoning Ordinance is hereby amended by adding a new Chapter 18Y, SPI25, Tuxedo Park Special Public Interest District Regulations which shall read as shown on the attached “Exhibit A”.

Section 2: That the Official Zoning Map of the City of Atlanta is hereby amended by changing the designation of all those properties located within the Tuxedo Park Special Public Interest District so as to add SPI-25 to the District Designation. Said District shall be as shown on the attached “Exhibit B”. That the maps referred to, now on file in the Office of the Municipal Clerk, be changed to conform with the terms of this ordinance.

Section 3: That all ordinances or parts of ordinances that conflict with the terms of this ordinance are waived to the extent of the conflict.

Sec. 16-18Y.001. – Scope of Provisions.

The regulations set forth in this chapter, or set forth elsewhere in this part, when referred to in this chapter, are the regulations in the SPI-25 Tuxedo Park Neighborhood District. Whenever the following regulations conflict with provisions of Part III Code of Ordinances – Land Development Code Part 15 – Land Subdivision Ordinance or Part 16 – Atlanta Zoning Ordinance, the more stringent regulation shall apply.

Sec. 16-18Y.002. – Statement of Intent. The intent of this chapter is establishing the SPI-25 Tuxedo Park Neighborhood District is as follows:

Sec. 16-18Y.003. – Regulations.

1. Subdivision Requirements.

a. The Tuxedo Park neighborhood, as defined by the City of Atlanta, shall be considered a historic neighborhood for the purposes of Part 15 of the Land Subdivision Ordinance. All subdivisions within this district shall not be subject to Sec. 15-08.002(a)(2) and Sec. 15-008(5)(d) of the Land Subdivision Ordinance, but shall meet the following requirements in addition to all other requirements of the Land Subdivision Ordinance:

b. All new lots shall be oriented so that the shortest side of the lot faces the street.

2. Development controls.

a. Setbacks:

Buckhead’s Tuxedo Park has long sought to draw a line in the sand against subdividing lots in the neighborhood. But a local developer is trying again, and it is a showdown that may be a defining moment for both sides.

Benecki Homes is seeking to subdivide 3655 Tuxedo Road, at the corner of Woodhaven Road, into two lots. The existing lot contains a Tudor-style home dating to 1929. The new lot would be drawn on what is now a swimming pool and tennis court that face Woodhaven. The existing lot is 2.66 acres and, like most of the neighborhood, is zoned to allow lot sizes as small as 1-acre. Subdividing the lot would comply with all zoning requirements, but that did nothing to convince neighbors who joined in on a recent NPU Zoom meeting to not oppose the plans. It was voted down 58 votes to 1. The applicant, Stan Benecki, was the lone “yes” vote.

The proposal “does not conform to the recognized ‘historic character’ of the Tuxedo Park neighborhood,” argued Gloria Cheatham of the Tuxedo Park Civic Association (TPCA) in a letter to the Atlanta Department of City Planning (DCP). Exactly who is able to define and determine what the elusive definition of “Historic Character” means is what makes this story so interesting. Whether this subjective standard can supersede zoning code is soon to be determined. It turns out this is a story dating back 100 years.

Mass production of the automobile and a streetcar connecting downtown Atlanta with Buckhead resulted in a development boom. Developers carved up estates that had been on hundreds of acres into residential lots.

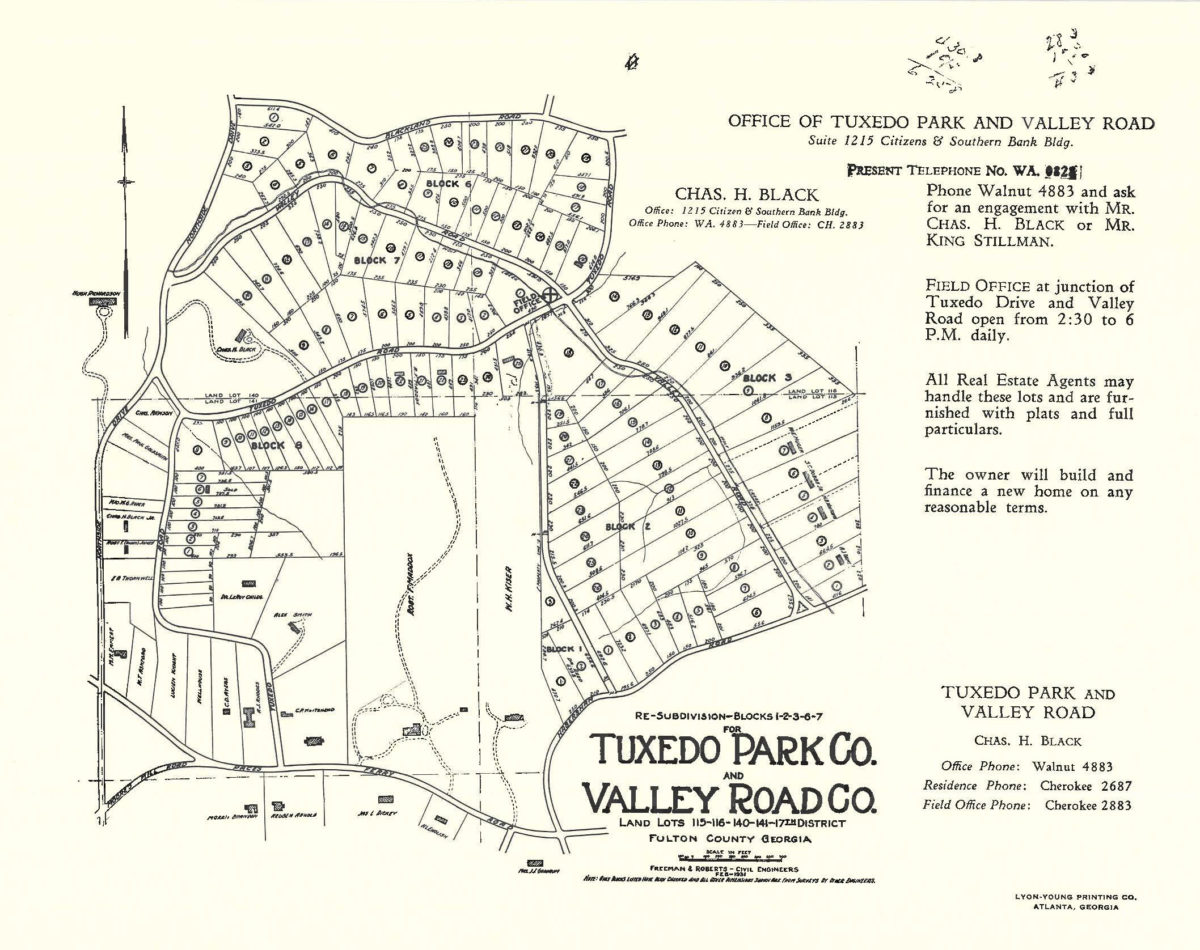

The idea of Tuxedo Park was conceived by a developer and a real estate agent who purchased 600 acres later developed into the Tuxedo Park neighborhood.

Dodie Stockton recounted in a history of the neighborhood how it came to be: “My grandfather was Charles H. Black Sr. He took great pride in telling his version of the acquisition of 600 acres north of Atlanta. He had lost a large sum of money in the Florida real estate market and returned to Atlanta in 1911. He borrowed a Cadillac automobile and a chauffeur and he went and got his banker friend and took him to ride and borrowed the money to purchase 600 acres which was a little bit north of Atlanta. He lived on that 600 acres all of his life and the 600 acres became Tuxedo Park.”In 1923, Charles Black Jr. joined the family development business as a builder and real estate agent. He constructed a large Tudor home for his family to demonstrate to potential clients what he was capable of building. This home still stands at 225 Valley Road, on the corner of Tuxedo Road. Tuxedo Park soon became a neighborhood of choice for wealthy families of the day and remains so to this day.

From the 1950’s through 1990’s, several new cul-de-sacs were developed in the center of the neighborhood with most lots coming in just above the 1-acre requirement. Dozens of lots were carved off larger estates throughout Tuxedo Park, and many new landmark homes were built on them. Values in the neighborhood continued to soar.

Between1989-1990 a proposal was created to have Tuxedo Park listed as a “Historic District” by the National Register of Historic Places. Some residents were opposed to the plan, concerned about the possible loss of property rights. They hired Carl Westmoreland to lobby against the designation, while Mary Norwood (then President of the TPCA) rallied support for the designation. Ultimately, the Atlanta City Council rejected the plan and it was never taken up again. “We had 400 in support of the proposal and only a handful opposed, but they had connections down at city hall,” said Norwood. In the years that followed, a group of neighbors often sought to deny subdivisions in and around Tuxedo Park. Resident and eventual City Council member Mary Norwood often led the charge. In cases where a proposed subdivision fit the zoning code, the developer usually prevailed.

In 2018 the “Pink Palace” on the corner of West Paces Ferry Road and Tuxedo Road received approval for a subdivision of its 3.5-acre lot into three lots. Two new lots of almost exactly one acre on either side of the existing 1926 Baroque mansion were approved by the City of Atlanta. This defeat was bitter for the opponents of subdivisions and galvanized their resolve. They needed to change the rules or make some new ones.

In 2020, the opponents of development in Tuxedo Park finally got their big break. The owners of a home on 3.4-acres at 3460 Tuxedo Road filed an application to subdivide the property into two lots. The subdivision went through the normal process of checks and balances. The TPCA submitted a letter in opposition.

On January 17th, 2020, Doug Young, Assistant Director of the City of Atlanta Office of Design and Historic Preservation, issued a determination; “In general, neighborhoods that are eligible for the National Register of Historic Places should be 50 years or older….Staff found that there were not enough remaining houses 50 years old or older to make the neighborhood eligible. Staff finds that the Tuxedo Park neighborhood, as it exists today, would not meet the criteria for being considered historic for the purposes of the City’s subdivision review process.”

With this determination, the subdivision application at 3460 Tuxedo Road was set to sail through the rest of the process. But then things went from procedural to political.

After a four-week behind-the-scenes campaign by subdivision opponents and some political machinations, a new letter was issued by Doug Young overturning his previous decision. A revised neighborhood map of homes and their ages had been developed with input from the TPCA which had calculated 53% of the homes in the neighborhood being 50 years old or older (a previous study by the applicant had claimed to show otherwise). In addition, the Office of Design Staff had taken a drive through the neighborhood to complete what they called a “windshield assessment”. Based on that car ride, and new map boundaries, Tuxedo Park would now be considered a “Historic Neighborhood” by the Office of Design based on their determination that it was now “Eligible to be listed on the National Register Of Historic Places”. Importantly, this gave individual city planners wide berth to deny subdivisions – even if they comply with zoning laws – based on their interpretation of whether the new lots would conform to the “historic layout, patterns, and design”.

Once Doug Young issued the letter stating the neighborhood had a historic designation, the zoning became secondary. The subdivision at 3460 Tuxedo was denied because “a side lot lines with an angle” was present on one of the two lots. Doug Young rejected the subdivision because “the vast majority of the existing lots in the neighborhood do not include such a configuration.”

According to Carl Westmoreland, the veteran zoning attorney who represented the applicant and helped defeat earlier attempts to list the neighborhood on the Historic Register: “The City’s position is that the City can determine “eligibility” as Mr. Young attempted to do is not consistent with federal regulations. Part 60 of Title 36 of the Code of Federal Regulations authorizes the Secretary of the Interior to maintain the National Register of historic sites and establishes the process and criteria to be followed in doing so. The regulations are explicit that eligibility for inclusion in the National Register is the sole province of the Keeper of the National Register of Historic Places.” While the owner of 3460 Tuxedo is appealing the denial in court, the Tuxedo Park Civic Association finally had the “win” that had eluded them for so long.

While Benecki’s recent subdivision application at 3655 Tuxedo was soundly defeated at the NPU level, that vote is merely an indicator to the city of how the neighbors feel. City planners are still bound to follow laws and zoning code in making their determination. Just three days after the NPU vote, Matt Adams, Assistant Director of the Atlanta Office of Design – Historic Preservation, issued a ruling to approve the subdivision proposal. Even when viewed through the “Historic Character” lens, which Gloria Cheatham of the TPCA had successfully argued was now a precedent, Adams found the proposed rectangular lots were larger than approximately 35% of existing Tuxedo Park lots and as such “would conform to the existing neighborhood’s layout, patterns, and design”. This effectively set Benecki up for final approval of the subdivision and he immediately started site preparations that were listed as city conditions for such approval, including tearing down a carriage house that straddled the new boundary line. Unbeknownst to him, things would soon take a familiar turn.

While Mary Norwood contributes the tireless energy and political connections for subdivision opponents, it is Gloria Cheatham, past president of Tuxedo Park Civic Association and retired attorney, who has proven to be their greatest asset in recent years. Cheatham brings an art of persuasion so convincing that city planners wither under the weight of her letters, opposition lawyers struggle to keep pace with her oral arguments, and developers marvel at her ability to make her point. It was one of her signature letters on January 3, 2023 to Matt Adams that once again turned this issue back in favor of subdivision opponents. Across the five-page letter Cheatham argued that, although the new lot created by Benecki did fit all other criteria, it was simply not long enough (her emphasis, not mine) to fit the pattern of the neighborhood.

Matt Adams issued a new determination on January 6th; the subdivision would be rejected because the new lots would not be long enough to conform with the neighborhood’s “layout, patterns, and design”. No definition of what would be “long enough” was provided.

Benecki received the news, an unwelcome surprise to him, just as he was finishing demolition of the carriage house on the property. “I bought this property for $4 million based on the understanding that it could be divided into two lots,” he told me. “How can they say this lot is too small for the neighborhood when it is larger than 35% of the existing lots?”

While Benecki has not made it clear what his next steps will be with the property and whether he will challenge the ruling, the indefatigable Mary Norwood is already doubling down. Perhaps aware of the tenuous footing on which these recent subdivisions have been rejected, she submitted “Walk-In Legislation” three days later to the Zoning Committee of the Atlanta City Council. Her proposed legislation would establish new zoning restrictions applicable only to Tuxedo Park. Using a new concept called “zoning strings”, the legislation would enact the following rules in Tuxedo Park:

The effect of these two rules combined is that any new lot of record would have to be at least 300 feet deep and would have a front building setback of at least 150 feet. The most restrictive front setback in the current zoning code is 60 feet.

In a video recording of the Council meeting on January 9th, six Council members and city staff meet in the otherwise empty chambers. Around 22 minutes into the meeting, Norwood’s proposal to revise the zoning code for the neighborhood is read out and she calls for a vote. After the vote, which was unanimous in favor, Council member Matt Westmoreland speaks up, “Actually, we will need to reconsider this because what we should do… this committee shouldn’t approve it yet. We need to send it to the ZRB (Zoning Review Board) and NPU, so I m sorry I’ll have to ask you to reconsider.” The full committee then votes unanimously, again, to rescind their approval and to send the proposal for review and public comment to the ZRB and NPU-A. The NPU meeting will be March 7, 2023 07:00 PM (the original meeting February was delayed), Click Here to register and join the meeting. The ZRB will take up the issue at a meeting on March 9th at 6pm in city hall council chambers. If the proposed legislation makes it past these two boards then it would go for a full city council vote that could make it law.

While this story has spanned decades and has had numerous twists and turns, it clearly is not over yet. For Mary Norwood, passage of her legislation would make it almost unfeasible for anyone to develop additional lots in Tuxedo Park due to the unprecedented setback requirements. She would finally have the victory she has been after for 33 years. The consequences could be more far-reaching than intended. While a seeming boon to NIMBY’s, a neighborhood-by-neighborhood patchwork of zoning regulations would have a chilling effect on future development, additions, and renovations throughout Buckhead and across the City of Atlanta.

The issue at stake almost always boils down to two perspectives: Property owners who wish to exercise their private property development rights to capitalize on millions of dollars in potential profits that a lot in Buckhead can bring, versus those who see new lots being created in the neighborhood as a threat to its historic character and their enjoyment of it. We may soon know which one will prevail.

Authors note: I have a particular interest in the issue of land use, zoning, and private property rights in Tuxedo Park. While I have never had any ownership in any subdivision process, I have owned multiple homes in Tuxedo Park and have brokered countless sales in the neighborhood for clients on all sides of this issue. Despite this web of relationships that are inevitable, I have made every attempt to be fair in my reporting on this issue.

What a difference a year makes in City rezoning.

In late 2021, Buckhead was an epicenter of fury about proposed zoning and land-use changes aimed at boosting density and affordability in some single-family neighborhoods.

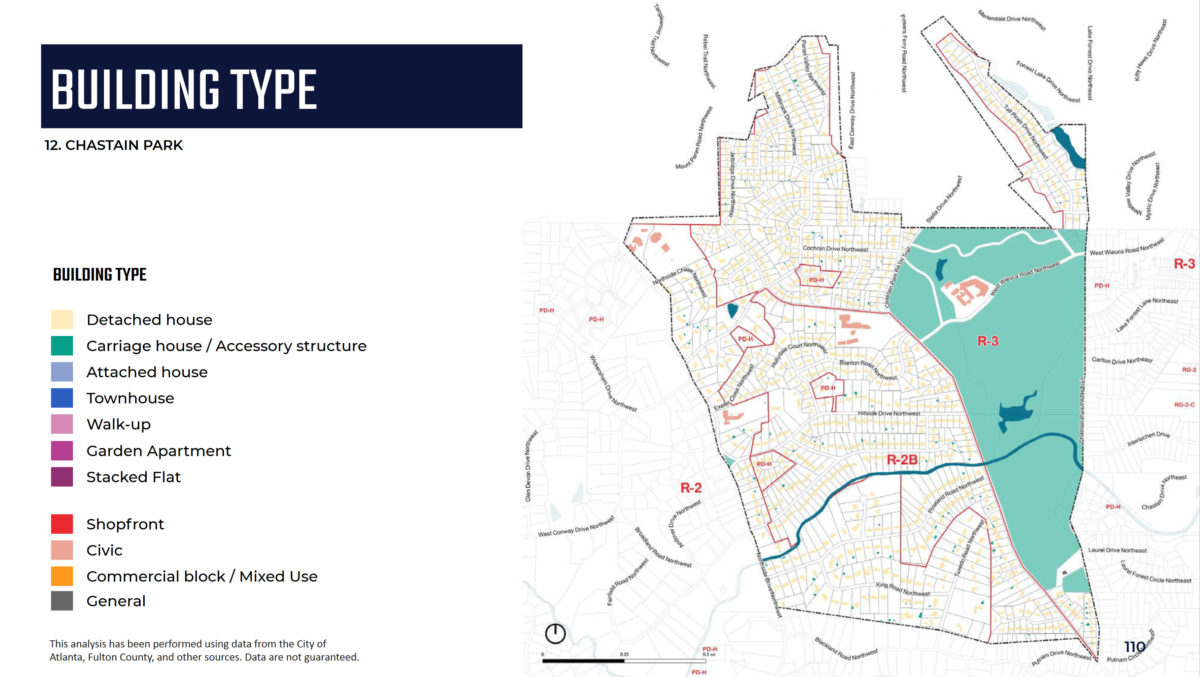

By late 2022, a course correction under a new mayor and City Planning director had Buckhead’s District 8 City Councilmember Mary Norwood so pleased, she’s proposing Tuxedo Park as a test case for one of the new zoning code concepts – one that would keep density low.

“I am a big proponent of the process and the intent [and the] vision so far,” said Norwood.

Atlanta’s zoning code hasn’t been fully updated since 1982, a problem the City has inched toward fixing for years. A preliminary step was revising the Community Development Plan (CDP), a planning policy document upon which zoning code is typically based. Dramatic and complicated changes to the draft CDP – including ones aimed at allowing more density in single-family neighborhoods – last year drew complaints from Buckhead’s Neighborhood Planning Units (NPUs) and criticism from a state regulatory agency.

Meanwhile, the Department of City Planning (DCP) was proposing several highly controversial zoning code changes also aimed at density, particularly allowing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in more single-family neighborhoods. Proposed under former Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms and former City Planning Commissioner Tim Keane, the legislation aimed to address historic, racism-based inequity and increase affordability. But their issuance in a nontransparent and confusing fashion fed even more controversy in many neighborhoods and particularly helped to fuel the Buckhead cityhood movement.

Amid outcry, the City stepped back from such proposals and approved a reduced version of the CDP — known as “Plan A” — due to a state legal requirement for an update every five years. The City promised more public input into a full CDP revision, which is currently projected to wrap up in 2025.

Meanwhile, Bottoms and Keane have left. Mayor Andre Dickens has been far more sensitive to neighborhood concerns and new Planning Commissioner Jahnee Prince is leading a department that is going slow on the CDP and instead focusing on a rewrite of the zoning code dubbed “ATL Zoning 2.0.”

Led by the urban planning consulting firm TSW, that zoning rewrite is in the midst of a public workshop phase. TSW’s Caleb Racicot said at a Nov. 29 workshop that “we’ve got to take this at the speed of trust” to ensure neighborhood input.

Revisions of CDPs and zoning code are typically done more or less simultaneously, but the CDP often is finished first, as code follows policy. The City is doing the reverse this time, specifically saving any major changes to zoning districts for the CDP rather than code. That’s clearly to delay the political heat and focus on relatively dry zoning code. Racicot said the rationale for not changing the districts in the code is “how passionate people can get about zoning changes on one particular property,” especially if it’s “changing density and use.”

Norwood says that “when you’ve got two-thirds of the NPUs unhappy with the CDP,” it makes sense to start with the code instead.

However, the code ideas being floated would empower some of those controversial changes. Implicitly referring to density debates, Racicot said that some neighborhoods want change and others don’t. So TSW is proposing a new approach to district designations that would allow nuanced and localized options without changing the overall zoning.

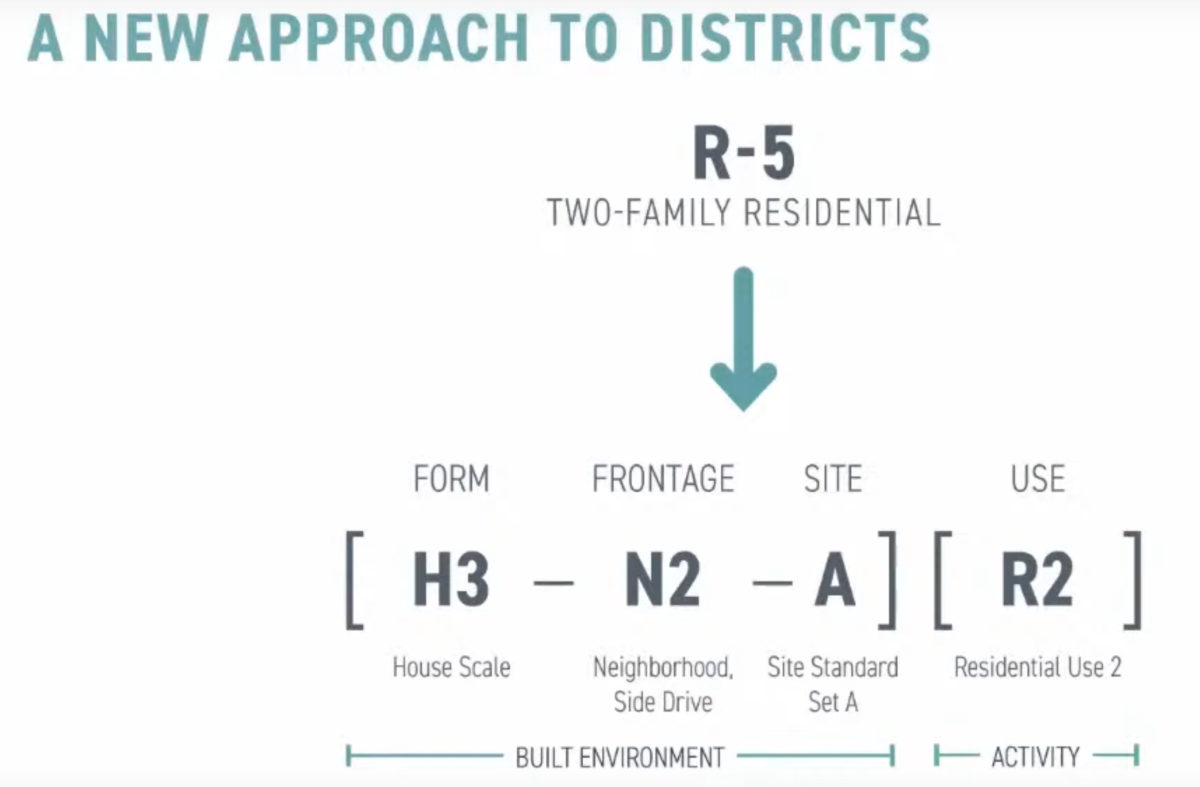

The idea is “zoning strings.” Current code designates districts by names that indicate the type of use that’s allowed, such as R-5 for a residential category, but in the body of the text also restrict other main features of zoning: form, frontage and site characteristics. The zoning strings concept is to keep all of those four elements separately named and controlled, so each can be changed like dials on an instrument panel to get more nuanced results. An example planners showed at the Nov. 29 workshop was “H3-N2-A R2,” where the designations refer to the form of a house, its frontage on a side street, the site development standard, and the residential use. Any of those individual designations in the string could be changed while leaving the rest.

It’s a newfangled idea, but also an old one – Racicot said Atlanta had a version in its 1920s code. (Incidentally, that’s the code whose explicit racism and its lingering effects on segregation and inequity is what Bottoms and Keane were trying to undo with some of the controversial zoning proposals.)

Racicot asked the public to suggest areas where planners could test some of the zoning concepts in pilot projects before they finish their work. That got Norwood’s attention. She thinks the zoning strings format is a way to tackle an issue that has bedeviled Tuxedo Park: subdivisions that change historic lot dimensions and patterns. She has submitted a City Council paper that would establish a zoning string format in the neighborhood under the existing concept of an overlay called a Special Public Interest (SPI) district. The site and frontage parts of the string would fine-tune the lot dimensions to avoid subdivisions.

“It is essentially a demonstration project, a pilot project, that will show the appropriate interpretation of what they have called a zoning string,” said Norwood. “… So we stepped up to the plate and they are on board.”

“I have liked what I have seen, and I am very grateful that the planning department saw this one ordinance – very simple, one page, one paragraph – that addresses an issue of concern to the specific neighborhood and there is a way that I can do this,” she continued. “Thirty years ago, it was either you had to be a historic district with all these regulations or there was nothing for you. So we have come a long way from that point of time in the city to where I can use an SPI for this one issue.”

It remains to be seen how that works out and what the public at large thinks of code proposals as the rewrite heads toward a final version expected in summer or fall of 2024. The process already ran into a snag with complaints about a survey that included highly technical language. However, there are many more opportunities for input, including three major workshop meetings continuing into April 2023. For full details, see the Zoning 2.0 website.

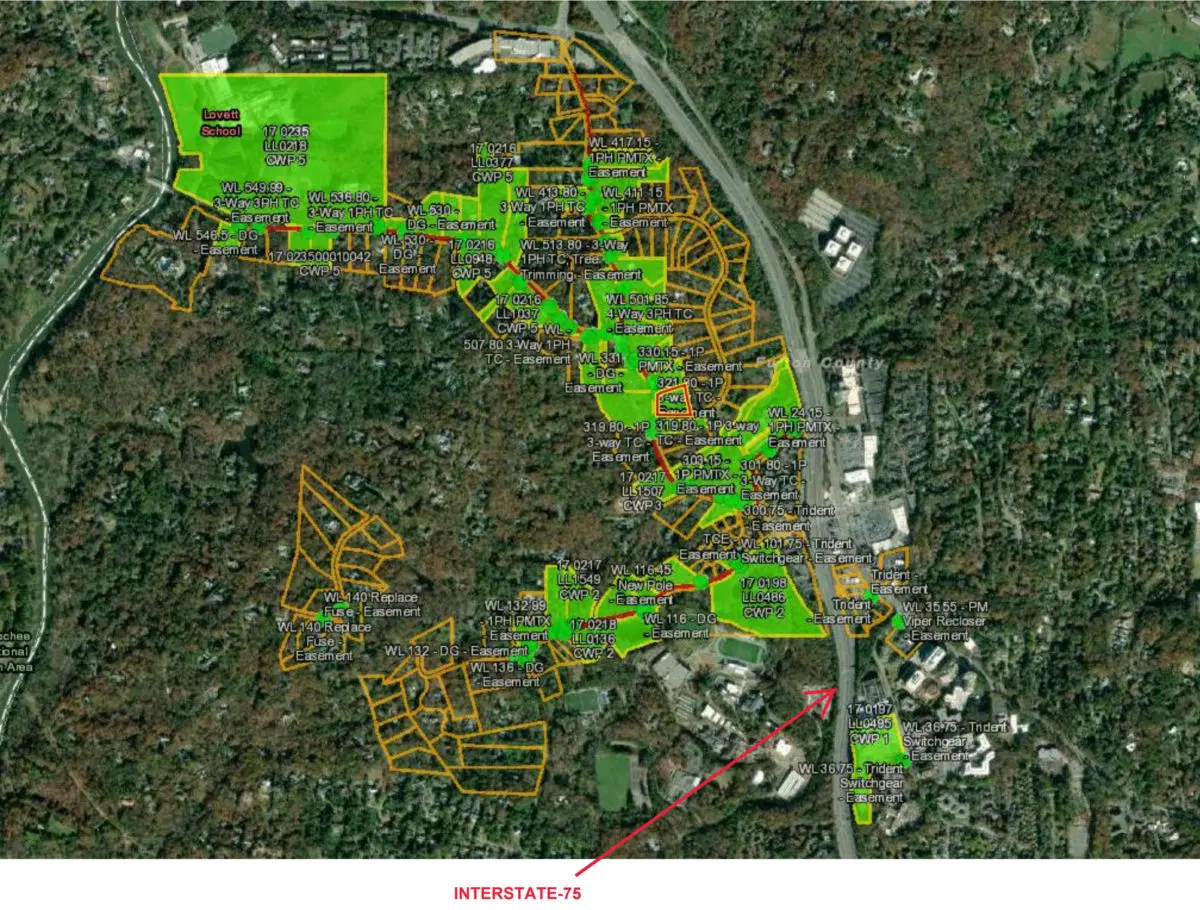

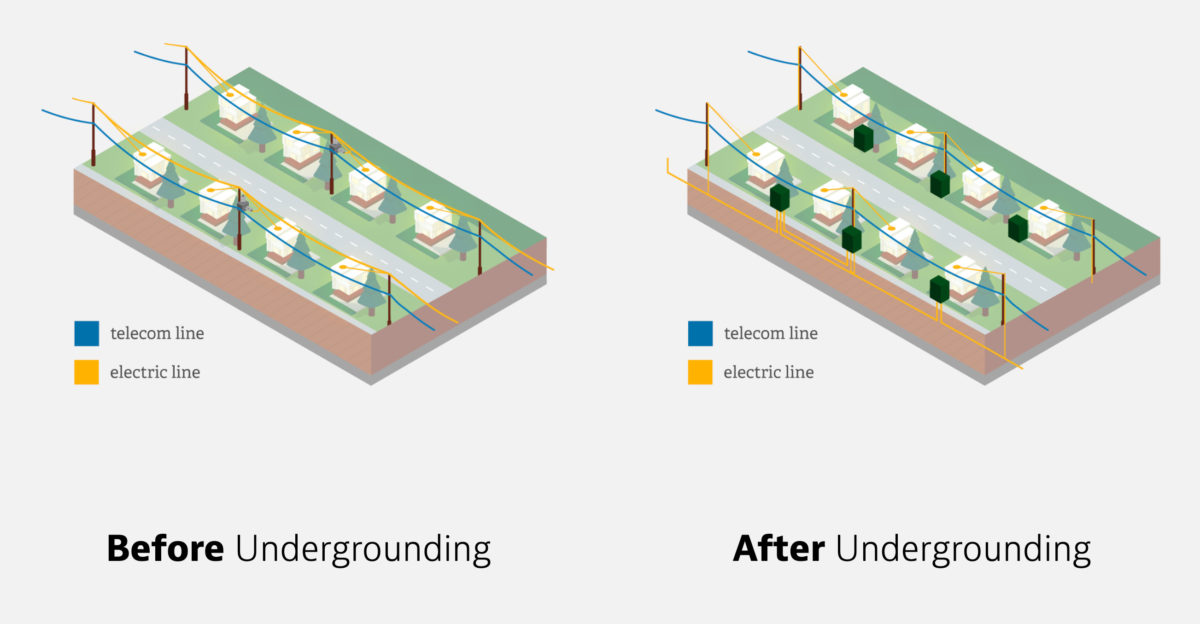

Georgia Power has plans to bury electric lines in several Buckhead neighborhoods starting this year as part of a multibillion-dollar plan to reduce blackouts. First, they need to secure the necessary easement by winning over property owners in the path of the project.

Buckhead’s impressive urban forest is a huge civic asset, but also means that storms – like the remnant of Hurricane Irma in 2017 – often topple trees into power lines. Burying – or “undergrounding” – the lines is a way to avoid that problem.

“Placing power lines underground makes the grid more resilient because they’re less vulnerable to storms and wind, but it’s not fault-proof,” said Georgia Power spokesperson Marie Bertot. “In areas prone to flooding, digging, root vegetation and other underground activity, it’s not always an option.”

Undergrounding is sometimes done for aesthetic reasons as well. But the Buckhead plan will leave existing poles standing to carry lines from the street to houses and businesses, and for use by telecommunications companies (AT&T, Comcast). According to one source, additional poles will actually be added to deal with the new web of connections. In rare cases where neither Georgia Power nor the telecommunications companies are using a power pole, it will be removed.

In addition, the underground system requires a series of transformers housed in familiar green metal boxes that will be installed in front yards and along sidewalks, so many residents will be hearing from Georgia Power contractors about purchasing easements for those devices.

The local work will cover the Paces Ferry, West Paces Ferry, and Powers Ferry roads corridors in such western neighborhoods as Chastain Park, Paces and Tuxedo Park, as well as part of North Buckhead between Ivy and Wieuca roads. Georgia Power aims to begin construction this spring and summer, with the work lasting approximately 12 months.

The work is just one part of Georgia Power’s “Grid Investment Plan,” a major, multiyear project of systemwide improvements. The goals are improving the reliability of Georgia’s electric grid and lessening the impact of any failures. The company is about two years in the first phase, for which it is spending $1.3 billion.

Improvements are not performed randomly. “We are making strategic grid investments, selecting project locations based on historical service and performance data to ensure that we are putting our resources in the right places to improve reliability,” said Bertot.

The grid has two basic components: transmission, where power is sent over long distances to localities, and distribution, which is sending the electricity into your home or business.

On the transmission side, the plan includes replacing wires and/or structures, and substation improvements as significant as full reconstruction.

On the distribution side, undergrounding is just one of several improvement tactics. Others include: adding “automated line devices” that automatically isolate outages to smaller parts of the grid; adding connections, which can provide a backup power source; relocating lines in hard-to-reach areas so that repairs are easier; and line strengthening, which can refer to a variety of upgrades in localized spots that make damage or other failures less likely.

Buckhead is also getting automated line devices and strengthened poles, according to Georgia Power.

Many other neighborhoods, such as Druid Hills, are getting similar improvements, including undergrounding.

Undergrounding requires various metal boxes to be set into the ground to provide power switching and delivery. In particular, a box called a “single phase transformer” has to be placed “every few homes” for delivery, according to Georgia Power’s website. Those are green boxes on a concrete pad that are roughly 26 inches high, 34 inches long and 31 inches wide. They are built on a concrete pad and need about 10 feet of clearance to be maintained on all sides.

There is not sufficient space for the boxes to be installed in the public right of way, which in residential areas typically means a narrow strip of lawn along the road. Acquisition subcontractors are now contacting residents seeking easements to install the devices, offering around $1,000 as compensation. If the initial offer is rejected, the offer escalates quickly and significant amounts have been reported.

The easements are all voluntary, according to Georgia Power, though it is less clear what happens if property owners refuse, especially on an entire street. The company’s answer is that in such cases it would “explore other project alternatives.”

The company says it aims for “minimal disruption” in installing such devices. But the work might require trimming trees, removing landscaping and digging up sidewalks and road trenching. Landscaping and sidewalks would be replaced by the company.

The undergrounding affects only the main distribution line, not the lines going to individual properties, so poles will remain for that purpose. Georgia Power also says it notifies telecommunications companies that may also use the poles about the work, but can’t control whether they also choose to bury lines. Any pole used purely for carrying a Georgia Power distribution line would be removed after the undergrounding.

Georgia Power provides extensive information about the Grid Improvement Plan – including frequently asked questions and construction maps – on its website.

The following are the general areas and timelines for undergrounding of lines in Buckhead, according to Georgia Power. All of the general areas include “most side streets in the area.”

Construction is well underway on this home by Macallan Custom Homes. The home sits perfectly on an 3/4-acre lot on prestigious Valley Road. This ideal location is walking distance from the restaurants, shops, and activities that make Buckhead Village such a desirable location.

Around back you will find a walkout pool (included!) and yard right off the main level. Enjoy this setting and view from your amazing 28’x14′ vaulted outdoor living room that doubles as a pool house and is sure to be one of your favorite rooms.

The architecture by Tim Adams is a transitional take on a classic English estate. At the oversized motorcourt entry you will be met by a handsome facade and an oval steel entry door. Inside you will find everything on your list….and more!The main floor features 11-12 foot ceilings and simply too many features to list here. The terrace level is finished to include a game room, bar, media area, guest suite, and massive “cross-fit” style fitness room. Upstairs is a large playroom surrounded by four bedroom suites PLUS there is a large guest/nanny suite (or the world’s best home office) accessed via a separate staircase above the 3-car garage. Call for more details, this one will be be presold with completion near the middle of 2023.

Tuxedo Park is the undisputed top-shelf neighborhood in Buckhead. The rich history of this area goes deeper than many residents may realize. This early Atlanta suburb was only woods and farmland at the beginning of the 20th century, but that quickly changed. Wealthy Atlantans began building homes along Paces Ferry around 1904, many used as summer or country estates with farm animals and extensive gardens. Tuxedo Park expanded North several blocks from there and has kept its refined Southern elegance ever since.

The Tuxedo Park Civic Association holds social events, hires private security officers, and generally keeps the neighborhood connected despite the mostly gated and secluded estates. With its historic mansions and picturesque landscaping, Tuxedo Park is aptly named for this sophisticated neighborhood of magnificent residences. Some of the finest estates in Buckhead are located in the prestigious Tuxedo Park neighborhood.

Although the city of Atlanta has grown to surround this once-remote area, the neighborhood still maintains an aura of seclusion and escape. The manicured grounds and varied architecture of the homes give the neighborhood a formal air befitting its name.

Buckhead Village District is truly the heart of Buckhead today. Renowned restaurants like UMI, The Iberian Pig, Atlas, and many more are within just a few blocks. You’ll find high-end retailers like Hermes and Jimmy Choo, along with local favorites like Buckhead Art & Co. and Warby Parker. Don’t forget world class hotels like the St Regis, and hip lodging options like the retro-inspired Kimpton Sylvan Hotel.

Buckhead Village residents can easily walk to Whole Foods, the Buckhead Theater, and all of the great taverns and bars in the Village. Upcoming establishments like Fetch Dog Park (with a bar!) and new fitness concept Pepper Boxing will further cement Buckhead Village District’s status as one of the best neighborhoods in town.

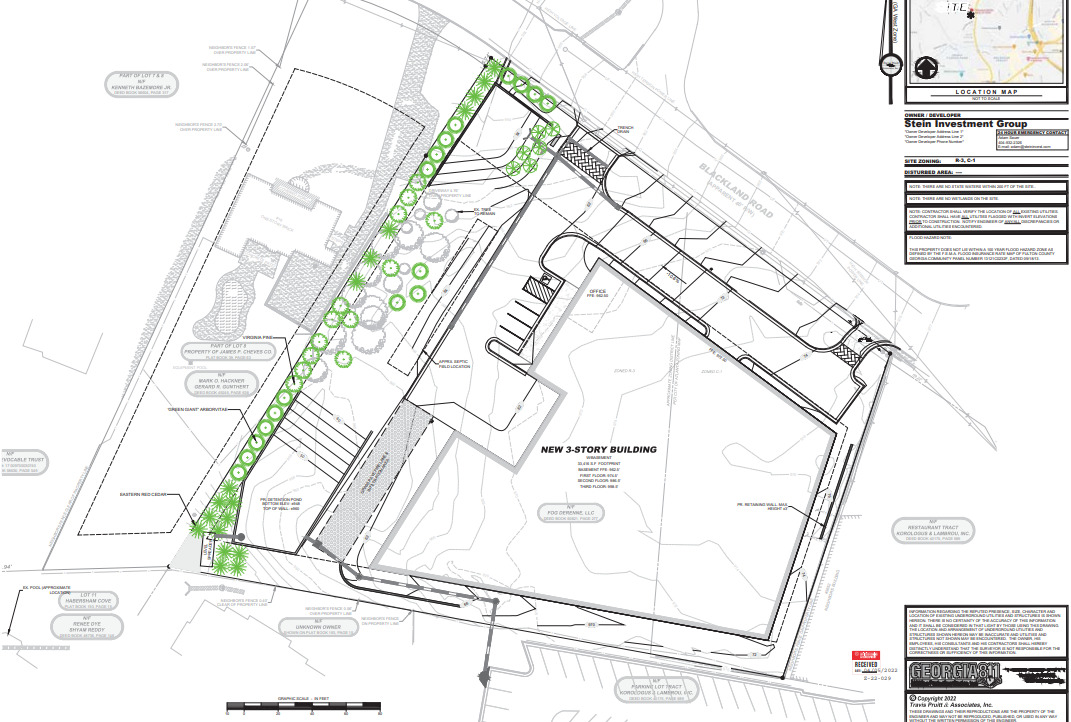

Stylish storage units have succeeded where million-dollar townhomes failed on a hot property behind Buckhead’s Landmark Diner.

Space Shop Self Storage won approval for zoning and land-use plan changes needed for its proposal at 10 Blackland Road at a May 3 meeting of Neighborhood Planning Unit A after winning extraordinary praise from the local civic association. That’s a big difference from 2018, when a luxury townhome proposal for the former landscaping company site was driven out by unhappy Tuxedo Park neighbors.

Sandy Springs-based Stein Investment Group, the would-be storage facility’s developer and owner, won over locals with major concessions. Among them are a huge wooded buffer, stormwater facilities that will handle the diner’s runoff as well, and a pledge to keep the adjacent 16 Blackland property – held by the same owner – permanently restricted to single-family residential development.

“As you all know, I don’t usually have very nice things to say about developers,” Gloria Cheatham, president of the Tuxedo Park Civic Association, told NPU-A before calling Stein a “huge exception” and a “pleasure” to work with.

The 2-acre property sits about 80 feet down Blackland from the intersection with Roswell and Piedmont roads. Formerly home to Harold E. Bailey Landscaping, it is largely undeveloped and wooded.

Located on a busy commercial corridor and the edge of Buckhead’s most exclusive neighborhood, the property is a hot item for developers – and a crucial transition zone for current residents.

In 2018, Monte Hewitt Homes proposed packing 23 for-sale townhomes onto the site. That drew fire from neighbors concerned about increased stormwater runoff in an area already beset by flooding, and about the precedent for denser housing in a neighborhood known for its expansive estates.

At first glance, a three-story storage-unit complex doesn’t sound much better. But Stein made many concessions, starting with a design that hides the use behind an office-building style facade.

More important to the neighborhood were some extraordinary deals, including establishing a 65-foot-wide, tree-lined buffer – covering roughly a half-acre – between the site and 16 Blackland. Stein’s Jason Linscott said the developers are “effectively creating this hard line permanently” because it would be protected with a conservation easement. Cheatham said the easement would be controlled by a nonprofit that also owns a neighborhood park at Tuxedo Road and Knollwood Drive. The single-family zoning for 16 Blackland also would be deed-restricted.

Also impressing the neighborhood was a promise to create a stormwater detention system about 50% bigger than required to handle some of the diner’s runoff as well as that of the storage facility.

Stein agreed to several other stipulations, such as restricting the operating hours. A landscaping plan includes street trees along Blackland. The plan has two curb cuts on Blackland: a main one directly across from that of a Walgreens pharmacy and a secondary one close to the Roswell intersection that is supposed to be right-turn-exit only.

The property is split between two zoning areas, one commercial and one residential. Stein is seeking to rezone it as an office/industrial category that would include this type of storage facility. That also requires changing the underlying land-use plan.

NPU-A members in attendance approved both requests in 14-0-1 votes. Those votes are advisory to the City, which is still reviewing the project.

Buckhead’s Atlanta Police Department precinct is seeing a changing of the guard as its current commander has received a promotion to deputy chief.

Andrew Senzer, who has led the Zone 2 precinct since November 2019 with the rank of major, will head APD’s Strategy and Special Projects Division, he announced at an April 7 meeting of the Buckhead Public Safety Task Force.

Major Ailen Mitchell, who has served as Senzer’s assistant since 2020, will be the new Zone 2 commander, Deputy Chief Timothy Peek said in the meeting.

The transition will happen on April 14, according to APD. The current head of the Strategy and Special Projects Division, Deputy Chief Darin Schierbaum, is being promoted to the vacant position of assistant chief of police.

Senzer was Buckhead’s police commander through the historic COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying crime spike, including the May 2020 rioting and looting in local business areas that spun out of Black Lives Matter protests about the Minneapolis police murder of George Floyd.

He also led through the beginning of the Buckhead cityhood movement that based itself on crime concerns. While crime spiked, Senzer took a zero-tolerance approach and Buckhead continues to have the city’s lowest crime rate.

“It really has been an honor to serve as the commander of Zone 2,” Senzer said in the task force meeting. “In my 26 years [in policing], this has probably been the most challenging assignment I’ve had.”

He said his new role will be “a little behind the scenes” but that he will “not be a stranger” in Buckhead.

Peek said APD is “ecstatic” about Senzer taking on the deputy chief role.

Mitchell, according to his APD biography, has been with the department since 2006. He previously commanded the SWAT team and, like Senzer, once served on the Red Dog unit, an anti-drug squad disbanded in 2011 after controversial incidents like an illegal raid on the Atlanta Eagle gay bar. Among his other work was the Gang Unit and the Auto Theft Task Force.

Mitchell became Zone 2’s Criminal Investigations Unit commander in 2018 and its assistant commander in 2020.

Zone 2 is headquartered at 3120 Maple Drive in Buckhead Village.

Update: This story has been updated with information from APD about the transition.

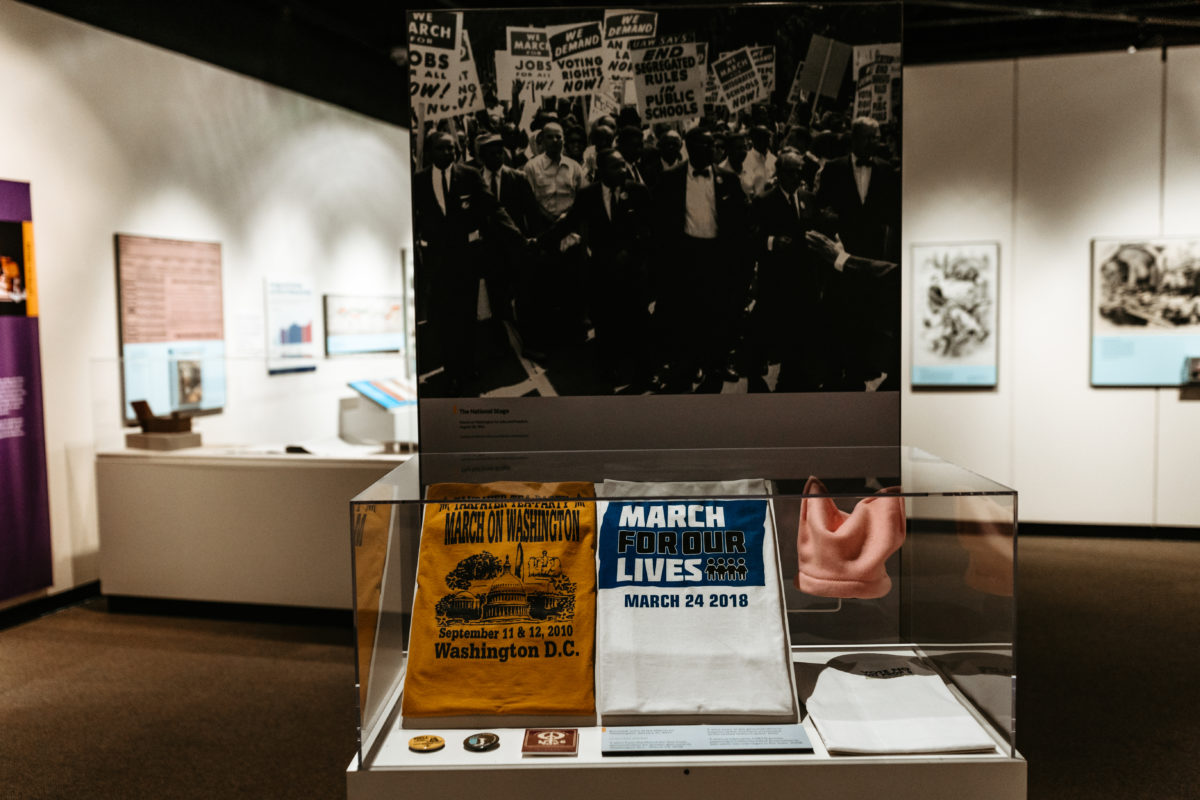

From last year’s attack on the U.S. Capitol to the ongoing invasion of Ukraine, it’s a tough time for democracy.

Then again, it always has been. The United States, the world’s leading light of democracy, has often failed to live up to its own ideals and has faced major threats from within and from other nations alike. The founders fretted constantly about the survival of a democracy that, come 2026, will celebrate its 250th year since the Declaration of Independence.

The Buckhead-based Atlanta History Center is co-founder of a national effort to not only celebrate that big birthday, but also to engage communities in the meaning and practice of democracy. A kickoff exhibit that you can catch through March 23 is just the start of multi-year local programs that also marks another 2026 anniversary: the center’s own centennial.

“The idea is, we’ve never been perfect, it’s always been hard, and people have always had to work at it,” says Sheffield Hale, the center’s president and CEO, reflecting on American democracy. “And you can be either a part of the solution or let somebody do it for you or do it to you.”

Since November, the center has hosted “American Democracy: A Great Leap of Faith,” a touring exhibit from the Smithsonian Institution that is customized with local artifacts. The center has paired that with community discussions and other events related to voting, civil rights and “community leadership” that Hale says is one outgrowth of America’s democratic culture.

But that was just the beginning of a five-year program leading up to the 250th, some in the works and some yet to be determined. Locally, the center already has scheduled a “Civic Season” program this spring and summer, focused on Juneteenth, the celebration of the emancipation of enslaved African American people in the U.S., and the country’s birthday on the Fourth of July.

“‘Civic Season’ is between those two anchors, and how they related to each other and don’t relate, and [how] people have different relationships and points of view about both of those holidays,” said Hale.

The center is playing a key role in a much larger effort of more than 100 affiliated history museums and organizations around the country, under the banner of a nonprofit called Made By Us. The group exists solely to crafts programs related to the country’s 250th birthday, or “semiquincentennial.” The center is on the steering committee, along with the National Archives Foundation and museums in Detroit, Pittsburgh, Miami, Missouri, New York, Oklahoma and Virginia.

Made By Us is still working on programming ideas, but Hale expects them to be deeper and more nuanced than the nation’s bicentennial celebration of 1976.

“I think what we saw in the bicentennial was just celebration, which was great. We certainly needed it. We certainly need it now,” he said. “But I think now it’s going to be more reflection and understanding in addition to the celebration.”

That includes acknowledging a democracy that often failed to include everyone, up to and including the atrocities of slavery. The approach may also mean adding notes of fragility, Hale says, to marking “250 years of a democracy that a lot of people — at the time and since — thought wouldn’t survive.”

For Made by Us, Hale says, “The target audience is 18 to 30 for this group, and it’s about civic engagement and what you can do — what is your vision for America?”

At the local level, the center is already focusing its programming on “building community” — meaning gathering people to discuss a book or civic topic, like voting rights and citizenship, to bridge differences and learn about ways to join community groups. Part of the lesson about democracy, Hale says, is “that you can participate in all kinds of ways, and it’s not just voting.” And maybe most important to “frankly, not take it for granted.”

“We like to say we’re talking more about methodology than ideology,” Hale said. “This is not a right-versus-left or blue-versus-red issue. It’s an American issue.”

As a museum, the center’s role is to “bring the facts to the table,” says Hale. But of course, history is rarely that simple or apolitical. “There’s never been an agreement on what our history was and is and what it means,” Hale acknowledges.

But the center also offers the “lens of history” — an opportunity to look back at successes, failures and mixtures of both long past without “being inflamed by the current moment,” as Hale puts it. “That’s one way you can approach history and sort of get past the partisan entrenchments people have.”

The real challenge for exhibit-creators is the substance. “How do you explain to people the genius of this democracy and the fact that it can be improved and has been, structurally and otherwise?” asks Hale.

And in particular, how to do that in a time when people may feel despondent or cynical in a time when fundamental institutions are being questions, from the Capitol attack to talk of packing the U.S. Supreme Court. History, as always, offers the opportunity for perspective.

“Things have been worse. We had a civil war,” says Hale. “Don’t wring your hands and say, ‘What am I going to do?’ Just do it. It’s there for you to do.”

For more about the “American Democracy” exhibit and other current and future programming, see the center’s website at atlantahistorycenter.com.

Nearly eight years have passed since an incurable killer of a beloved garden plant was first found in Georgia, lurking in a Buckhead lawn. Now boxwood blight has spread to devastate historic gardens and local landscapes across the country, while science is starting to catch up to the tricks of the fungal infection behind it.

Chris Hastings, owner of the Chamblee-based tree care firm Arbormedics, has been battling the blight in Buckhead gardens from Day One. He summed up the current state of affairs: “Is it bad? Yes. Has it gotten worse? Yes. Is it now commonplace on almost every street in Buckhead? Yes.”

However, Hastings adds, it also has not wiped out the plants as was originally feared. “But over all that time… it comes in waves,” he says, noting a particular blight-battling hint in its link to rainfall and moisture. “And really we’re still trying to figure out, what are those key moments? Because it’s not always as clear as you would expect.”

“The boxwood is such a beloved plant. It’s the aristocrat of the Southern garden.”

Chris Hastings, owner, Arbormedics

Jean Williams-Woodward is a University of Georgia Extension plant pathologist who was on the team that first identified the blight on boxwoods on that Buckhead property back in 2014. She says that “we’re still finding out things about this disease.”

The future she sees taking shape — much like the famously sculpture-friendly boxwood itself — is one where improved practices, disease-resistant breeds and a shift to other types of landscape plants will contain the blight.

Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) is a type of small-leafed, evergreen plant native to Asia that for centuries has been popular nearly worldwide as an ornamental. In tree form, it makes for stately, pillar-like entrance ornaments. It also takes well to being shaped with trimmers and is hugely popular for rectangular hedges — which is how the plant got the “box” name. The English and American varieties are wildly popular cornerstones of the traditional Southern aristocratic garden.

“In the South… it’s a plant that tugs on your heart,” says Williams-Woodward. And on your purse-strings, too — for nurseries and landscapers, “It’s a huge economic impact.”

“The boxwood is such a beloved plant. It’s the aristocrat of the Southern garden,” said Hastings, adding that’s why homeowners are willing to battle the blight instead of just getting replacement plants. “It’s been used for hundreds of years here. It’s been tied in people’s minds and their sensibilities to what a gorgeous Southern garden looks like. So it’s very hard to contemplate having a holly instead.”

This pretty picture started going bad with the original discovery of boxwood blight in the United Kingdom in the 1990s. An American infection was just a matter of time, and in 2011, the first U.S. cases were found in Connecticut and North Carolina nurseries. A Virginia nursery was the likely source of infected plants that led to that first known Georgia case in Buckhead in July 2014, on a private property that the experts won’t publicly identify for privacy reasons. The blight may well have been elsewhere in Georgia already.

The blight has continued to spread around the country and has become a major pest in historic gardens. Colonial Williamsburg, the famous historic area in Virginia, has been battling the blight for over five years in its collection of more than 8,000 boxwoods, many dating back a century or more, according to media reports. In the past year, major boxwood culling was carried out at the historic homes of poet and author Carl Sandburg in North Carolina and 19th-century politician Henry Clay in Kentucky.

“I’ve seen very historic gardens where every single plant has been lost… They just look like bare stems,” said Williams-Woodward.

The blight is a species from a genus of plant-infecting fungi. It kills boxwoods by causing their leaves to die, and can infect the stems as well. The blight can also infect other plants in the same family, including pachysandra and sweet box, according to Williams-Woodward, but is often not so lethal to those species. Some varieties of boxwoods have a degree of resistance, but the beloved dwarf English and American cultivars are not among them.

The fungus spreads by sticky spores that spew off the plant into the environment. Once it infects a plant, there is no known cure.

Williams-Woodward says the fungus has probably been around for hundreds of years, but was less prone to kill boxwoods in their original native areas of today’s Asia and Turkey, where the climate is drier. Wetter conditions are among the factors that make the fungus thrive.

In the first decade of battling the U.S. blight, tactics have shifted along with research and field practice, and even now there is some disagreement among experts about how the fungus spreads and should be fought.

Hastings notes that the early U.S. discoveries were inside mid-Atlantic nurseries and greenhouses, with plants packed closely together. That led to some assumptions about how transmissible the fungus was and that the air might be a major transmission method for its spores.

“So I do think there was a little bit of a misunderstanding in the early days about how contagious it, how lethal it is,” said Hastings. “So a lot of the original reports that came out and still linger were like, ‘If you have boxwood blight on your property, tear them all up and run screaming for the hills.'”

Yet today, he says, some original boxwoods continue to survive on the original Buckhead property that was the first known to have the blight. He said a second Buckhead property where the blight was found in backyard plants at virtually the same time still has boxwoods, too, including some within 100 feet of those with the outbreak.

What everyone agrees on at the moment is that moisture is key to the blight’s spread and that the disease can be managed with multi-pronged tactics. The situation can be illustrated with imperfect analogies to more familiar human diseases. Think of the blight as a lethal version of athlete’s foot that, like that fungus, infects and spreads explosively in wet environments. And like the coronavirus behind COVID-19, experts can’t currently cure or eliminate the blight, but can contain and manage the disease through a combination of treatment, built-up resistances, avoidance and new, safer cultural practices.

The blight erupts when the weather is wet and temperatures are moderate, said Williams-Woodward. The symptoms may retreat in hotter and drier months, she said, giving plant-owners a false sense of relief while the incurable infection remains.

Water is also now believed to be one major way the fungus spreads, as splash-back from rain or irrigation droplets hits other nearby plants. “Spores produced [by the fungus] are very sticky and they cluster together,” said Williams-Woodward. “So this pathogen or disease is not something that blows around in the wind. It’s mostly water-splashed.”

Hastings agrees that water is a major factor, saying that the earlier wind-spreading explanation never matched what he saw in the field. “We do not see it marching through a garden,” he said, explaining that the blight is almost always paired with heavy moisture from the environment. He said he often finds it tied to a broken rain gutter or — especially in lawns of well-to-do Buckhead homeowners — irrigation systems that are overused when rainfall is perfectly adequate.

“Irrigation, irrigation, irrigation is the number one reason that people have [boxwood blight] problems in Buckhead,” he said. He won’t even take on a boxwood client who won’t properly manage an irrigation system.

“I think we will end up in some kind of combination of planting less-susceptible varieties, plus some cultural practices … So we can manage this disease.”

Jean Williams-Woodward, University of Georgia Extension plant pathologist

Research shows that animals and humans may also be carriers of the spores, says Williams-Woodward. Boxwoods “actually smell like cat pee,” she said, and so may attract cats and dogs to mark them, resulting in spores getting on their fur to be spread to other plants. She said she saw one garden where boxwoods were blighted at the same level as the cushion on a patio chair that a cat slept on. Squirrels, rabbits and turkeys are other suspected spreaders.

Landscape workers may also spread the spores on their hands and equipment, Williams-Woodward said. She is currently conducting experiments on easy ways for landscapers to disinfect their gear before traveling to another property. Regular Lysol spray is looking highly effective, she said.

Hastings doesn’t buy it. He says animals and humans pale in comparison to water and another form of Buckhead lawn epidemic — the use of high-powered leaf-blowers that could blast spores all over surrounding properties. “I don’t think we need to be caging our cats and spraying down our landscapers,” he said.

What about spraying the plants themselves? After all, you can knock out athlete’s foot pretty fast with a can of fungicide from the drug store. Turns out it’s not that simple for boxwood blight, and Hastings and Williams-Woodward agree it’s no main solution.

There are fungicide sprays that can effectively reduce blight symptoms in a plant, said Williams-Woodward. But it requires regularly repeated application that few landscapers or arborists will perform, and that can be cost-prohibitive and raises issues of environmental pollution. Overuse of the sprays also could lead to the evolution of fungicide-resistance strains of the blight, she said.

Hastings said he’s one of the few local arborists who will spray for boxwood blight, but only as part of an integrated approach, as he also has environmental and best-practices concerns.

“Do we put every boxwood in town on a chemical crutch? Absolutely not,” he said, again emphasizing moisture as the main problem. “The key to getting ahead of this is thinking about your basement getting mold or mildew… You don’t run in there and start spraying Clorox everywhere. … You get rid of the water source.”

Another option is blight-resistant varieties of boxwood. Some already exist and others are being cultivated. But a note of caution on some of those, such as Japanese and Korean varieties: Williams-Woodward said they may be less able to catch and die from the blight, but can still carry and spread it, making them “sort of a Trojan horse.”

Her preferred tactic is to simply replace smaller boxwoods with a totally different species, like Japanese holly, and to prune the lower branches of larger ones to avoid the water-splash effect that may spread the spores.

Hastings says he’s hopeful the boxwood blight battle eventually will take a similar course as brown patch, a different fungal infection that affects fescue grass lawns. He said that landscaping veterans have told him about the brown patch plague in the 1980s, which coincided with a boom in lawn irrigation systems. Initially, he says, there was similar advice to landscapers about attempting to disinfect mower blades and the like. Today, he said, brown patch is manageable in a coordinated program of lawn management techniques that continues to allow fescue to be planted.

Williams-Woodward also looks to a future of containment and management. She said research continues on exactly how the blight spreads, the environmental conditions that favor it, how its biology works, and arborist techniques. “I think we will end up in some kind of combination of planting less-susceptible varieties, plus some cultural practices … So we can manage this disease,” she said.

For more details about boxwood blight, see the websites of the UGA Extension and the Georgia Department of Agriculture.

In the heart of historic Tuxedo Park lies a residence reimagined for the modern era. This beautifully updated home presents a masterful union of classic architectural grace and contemporary design, creating an unforgettable first impression.

From the striking iron entry doors to the gleaming hardwoods and robust whole-house generator, no detail has been overlooked. This exceptional property offers an unparalleled lifestyle, ready for you to make your own.

Blurring the line between indoors and out, a tranquil screened porch offers year-round enjoyment with the warmth of a wood-burning fireplace. Beyond lies a private resort-like sanctuary, where an expansive bluestone terrace surrounds a shimmering pool, all framed by a meticulously landscaped lawn.

The main level is crafted for hosting on any scale, with an effortless flow between multiple gathering areas. From large-scale celebrations in the banquet-sized dining room to quiet conversations in the sophisticated pub and lounge, every space invites connection and entertainment.

At the center of the home, the kitchen is a true showpiece of both style and function. A commanding L-shaped island provides abundant space for preparation and casual dining, while a caterer’s nook and a cheerful breakfast room with bespoke banquette seating ensure every meal is an event.

The upper level is a realm of quiet comfort. The owner’s suite is a lavish retreat, featuring two generous walk-in closets and a sumptuous marble bath designed for ultimate relaxation. Three additional bedrooms, each with a private en-suite bath, plus a versatile den provide ample space for family and guests.

A spectacular, newly constructed entertainment pavilion offers a dedicated haven for leisure and sport. Beneath dramatic vaulted wood-beam ceilings, you will find a cutting-edge golf simulator, a full-service bar, and its own bath—an amenity that truly sets this estate apart.

Privacy for visitors is assured with a charming and fully independent guest cottage. This self-contained home includes two bedrooms, a complete kitchen, a full bath, and a comfortable living area.