Most folks in Buckhead know there are horses stabled in Chastain Park. But even many locals don’t know the true humanitarian mission of Chastain Horse Park.

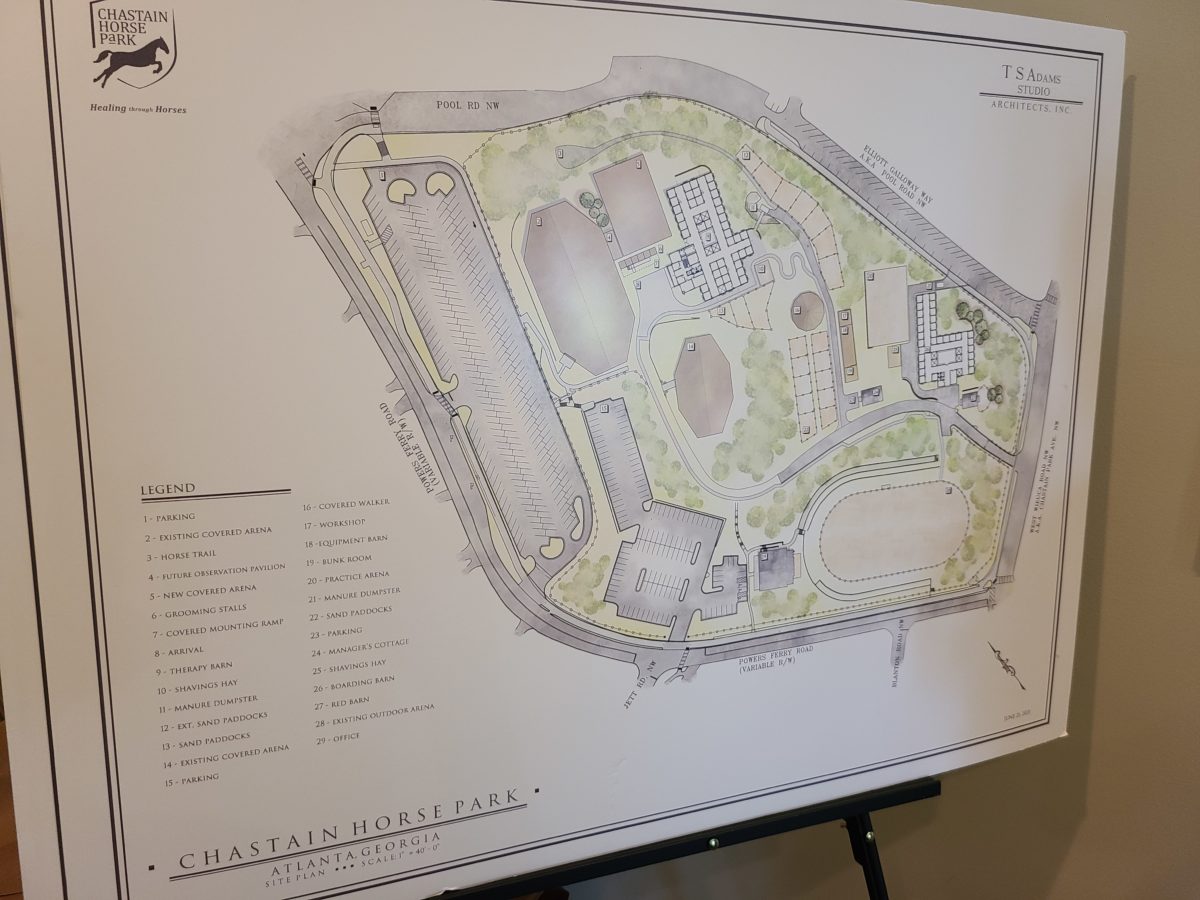

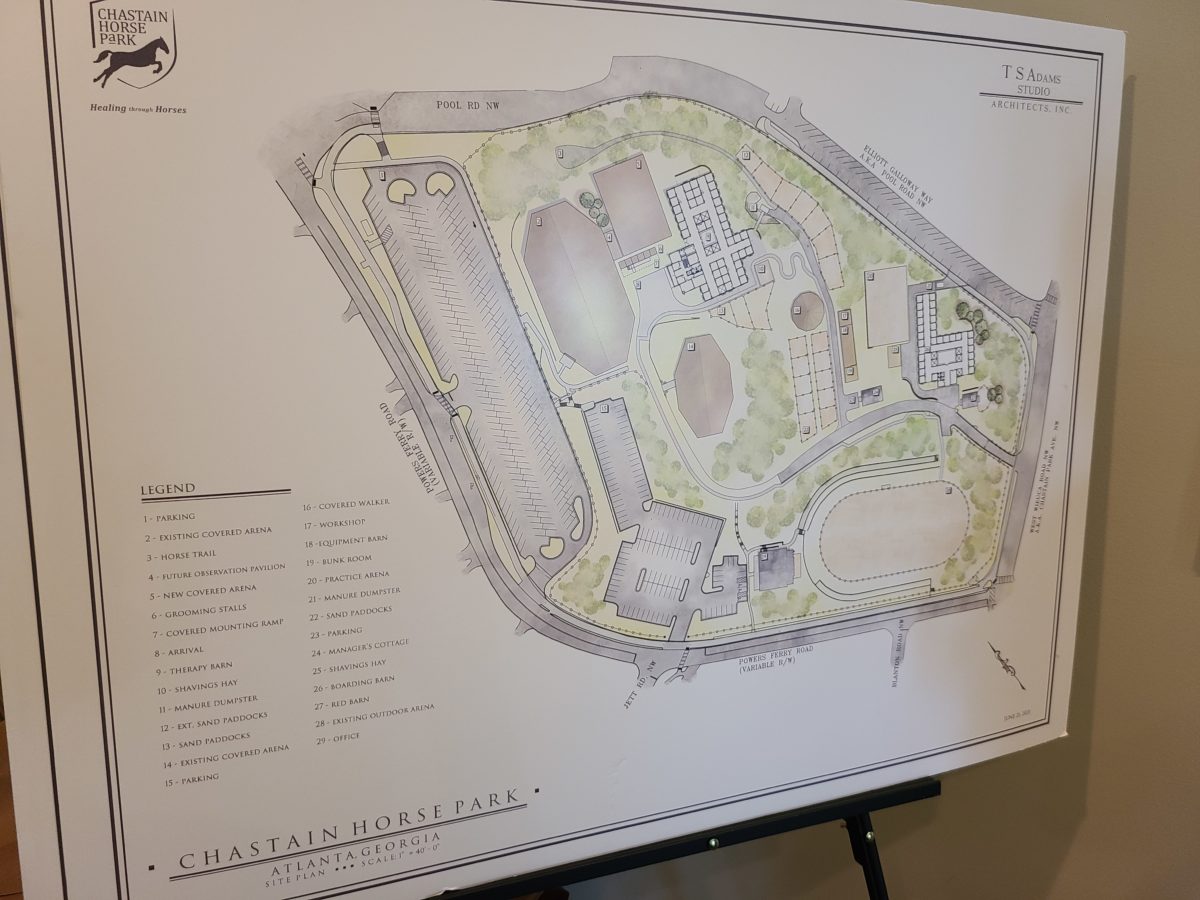

Created over 75 years ago as stables and riding grounds for wealthy horse owners, CHP now is an accredited center for “equine therapy” where people get help with physical, cognitive and emotional issues by bonding with the animals and other riders. And this week, it began work on a two-year, $8.9 million campus renovation to upgrade and expand such programs.

“The magic that happens here with our horses is incredible,” says CHP Executive Director Trish Gross, who led Buckhead.com on a facility tour shortly before work began.

CHP occupies about 15 acres of the City park at Chastain Park Avenue and Powers Ferry Road. It’s a private nonprofit that holds a long-term lease from the City that includes the right – and the responsibility – to build and pay for just about everything that happens there, contingent on continuing to offer therapy programs.

Back when the green space opened in 1945 as North Fulton Park, Buckhead was a rural area not yet part of the City of Atlanta, and many people had horses. The park included horse facilities, including a covered arena whose stone walls – likely built by workers in President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration programs – still stand today.

CHP still offers horse boarding, which is an important revenue stream, but that’s not its main function. Ditto for a large clubhouse known to the public as a place to host events. And while it stands within a public park, the private CHP is not a kind of horse zoo that anyone is free to wander. In fact, CHP has become what Gross calls “unfortunately, a best-kept secret” of the neighborhood.

Its true mission is the therapeutic programming, which serves hundreds of people each year thanks to a staff of 15 and many more volunteers. Those programs started so small sometime in the 1970s or ’80s, Gross says, that no one is really sure of their history. The formation of CHP as a formal nonprofit in 1999 was the beginning of a serious, nationally accredited program. In 2005, a team of physical and occupational therapists called My Heroes began working there, and in 2011 launched a second equine therapy program at Colorado State University.

The programs help people with a wide variety of challenges, such as cerebral palsy and autism. And a new psychotherapy pilot program will begin this fall. CHP has facilities and equipment specialized for therapy, such as a lift to help people who use wheelchairs to get onto a horse, and a “Sensory Trail” with various sensory engagement devices on posts or trees at horseback height. There’s also “Elvis,” a mechanical horse used to give therapy clients a taste of riding before trying the real thing.

“One of the tools that I use is the movement of the horse,” said CHP physical therapist Michelle Winer, explaining the motions can be soothing while also increasing a rider’s core muscle strength.

Most of the clients are youths, but about a quarter are adults. And they come from all over – with regulars hailing from as far as Macon – and across income groups. CHP subsidizes half of the programs and offers full and partial scholarships for those in need.

“It’s not 30327 serving 30327,” said Gross, referring to the swanky local ZIP code. “We’re 30327 making a difference for all of Atlanta.”

CHP also offers field trips for school students and at-risk youths, and a summer camp program that remains on pandemic hold but may return for 2023.

CHP owns the horses used in the therapy programs, which are selected for their temperament. Many of the horses are pets donated by individuals – including Gross herself, whose horse Dawson became part of the team in 2017. Combined with the privately boarded horses – many of them show horses – the total equine population any given day is around 50 to 60.

While these programs have boomed, the facilities have not. Most of the barns and paddocks date to the 1990s, when the nonprofit was formed, and are now inadequate and facing maintenance issues. Many even lack heating and air conditioning. And staff and volunteers work not only in the barns, but literally within stalls meant for horses.

“Our volunteer lounge is a stall,” said Gross. “The same stall is our kitchenette. The same stall is our volunteer coordination office.”

During the recent visit, a volunteer training was being held in the aisle of a barn, with a screen erected against the barred doors. Given the high-level accreditation and amount of programs, Gross said, the facilities are “subpar for what we do.”

Hence the “Healing Through Horses” capital campaign that, despite the pandemic, has raised most of the money needed to begin building new facilities. Demolition on one barn was scheduled to begin this week, with similar demolitions and reconstructions cycling over the next two years as programs and horses are shuttled between them. The main facility, the Therapeutic Horsemanship Center, will include stalls for 40 offices and many facilities for humans.

New paddocks are coming as well, while some facilities, such as the main arena and clubhouse, will remain untouched. There also will be housing for the on-site manager, Lori Barefoot, who currently lives in an apartment over one of the barns.

Some trees are coming down, Gross said, and will be replaced with new plants per City code. Part of the tree removal is required for an upgraded stormwater detention pond.

The end result will be modernized and somewhat larger facilities to handle an expansion of programs, though Gross says the number of horses should remain about the same. The plan includes a barn with stalls for 40 horses. Likening the project to a hotel, Gross said CHP is not going the cheap route but also not building something too fancy.

“We are going mid-level Marriott, not St. Regis or Motel 6,” she said.

It’s still a massive undertaking for a relatively small nonprofit. CHP still needs to raise about $900,000 to finish off the work. That’s on top of roughly $775,000 a year it needs to raise to maintain its $2 million operating budget. The next big annual fundraiser is coming in October.

A high-energy former tech business founder from the West Coast, Gross is used to raising money in the hard-bitten word of venture capital.

“This is whole different kind of investment,” Gross said of CHP fundraising. “When I’m raising money, I’m asking for an investment… in our community, in our integrity, in ourselves, in our humanity.”

Gross moved to the Chastain Park neighborhood in 2015 when her husband, a Cox executive, relocated to Atlanta. A horse-lover herself, she fell into CHP and eventually its leadership role. She is set on spreading better public understanding of its mission and the camaraderie that develops among clients, volunteers and horses.

“We’re a community. It’s a community focused around horses,” said Gross. And for those in it, whatever the stresses and changes in other parts of their life, “Everybody comes to the barn.”

For more about CHP and its capital campaign, see chastainhorsepark.org.

Situated in a quiet cul-de-sac in Highpoint neighborhood, 115 Franklin Place is one of the most convenient locations in Sandy Springs. Ride your bike to Chastain Park, and dine out in City Springs… Very close to the hospitals as well. All of this in a great family neighborhood. The minute you step inside this incredible family home you will fall in love!

This one has it all: high ceilings, lots of windows, hardwood floors, incredible square footage, and a lushly landscaped yard. You can sleep well knowing that the architectural roof and 3 of 4 HVAC systems were replaced in 2020, and the home comes with a premium home warranty!

Enter this light-filled home through double French doors and walk from the foyer into a fabulous home office/library with fireplace on one side and generous dining room on the other. Straight ahead is the bright living room with bank of windows and a gorgeous fireplace flanked by built-ins.

From here you step into a large chef’s kitchen with island, abundant storage in white cabinetry, granite counter tops, high-end stainless steel appliances, and breakfast area with so many windows! All of this is open to a bright, vaulted keeping room. A French door takes you out to an expansive deck overlooking a stunning backyard oasis with hot tub and fire pit area.

The oversized primary bedroom on main features a gorgeous trayed ceiling, hardwood floors, and a French door to the deck overlooking the lush backyard. The magnificent newly renovated master bath boasts separate soaking tub, frameless shower, double vanities, and stunning finishes.

4 additional bedrooms and 3 baths are all located on the upper level. All bedrooms are gracious with most featuring trayed or vaulted ceilings, walk-in closets and fresh, white baths.

Prepare for a surprise when walking down to the terrace level with high ceilings, and abundant square footage! On this level you will find a very generous bedroom and bath finished like those on the upper floor as well as a rec room perfect for pool or ping pong. In addition, there is a separate TV/media room with built-ins and French door to the charming covered tile patio overlooking the beautiful backyard. You will find 1,100 square feet of unfinished storage space down here as well, so there is plenty of room to expand the living spaces to fill your needs!

This beautiful home is less than two miles away from the recreation and social activities at Chastain Park.

Homeowners here will enjoy all that Chastain Park has to offer year-round. Chastain Park is Atlanta’s largest city park, and known by all as Buckhead’s premier park. The wide variety of competitive and recreational activities and entertainment venues hosted by Chastain Park include a swimming pool, a musical amphitheater where both pop and classical musicians entertain audiences outdoors, an arts center, tennis, gymnasium, walking trails, playgrounds, softball diamonds, a golf course and even a horse park – all of which appeal to athletic types and Sunday morning strollers alike.

The Chastain restaurant offers “refined comfort food” for residents and visitors alike in a beautiful setting across from the park.

Buckhead’s Atlanta Police Department precinct is seeing a changing of the guard as its current commander has received a promotion to deputy chief.

Andrew Senzer, who has led the Zone 2 precinct since November 2019 with the rank of major, will head APD’s Strategy and Special Projects Division, he announced at an April 7 meeting of the Buckhead Public Safety Task Force.

Major Ailen Mitchell, who has served as Senzer’s assistant since 2020, will be the new Zone 2 commander, Deputy Chief Timothy Peek said in the meeting.

The transition will happen on April 14, according to APD. The current head of the Strategy and Special Projects Division, Deputy Chief Darin Schierbaum, is being promoted to the vacant position of assistant chief of police.

Senzer was Buckhead’s police commander through the historic COVID-19 pandemic and accompanying crime spike, including the May 2020 rioting and looting in local business areas that spun out of Black Lives Matter protests about the Minneapolis police murder of George Floyd.

He also led through the beginning of the Buckhead cityhood movement that based itself on crime concerns. While crime spiked, Senzer took a zero-tolerance approach and Buckhead continues to have the city’s lowest crime rate.

“It really has been an honor to serve as the commander of Zone 2,” Senzer said in the task force meeting. “In my 26 years [in policing], this has probably been the most challenging assignment I’ve had.”

He said his new role will be “a little behind the scenes” but that he will “not be a stranger” in Buckhead.

Peek said APD is “ecstatic” about Senzer taking on the deputy chief role.

Mitchell, according to his APD biography, has been with the department since 2006. He previously commanded the SWAT team and, like Senzer, once served on the Red Dog unit, an anti-drug squad disbanded in 2011 after controversial incidents like an illegal raid on the Atlanta Eagle gay bar. Among his other work was the Gang Unit and the Auto Theft Task Force.

Mitchell became Zone 2’s Criminal Investigations Unit commander in 2018 and its assistant commander in 2020.

Zone 2 is headquartered at 3120 Maple Drive in Buckhead Village.

Update: This story has been updated with information from APD about the transition.

Springtime in Buckhead highlights some of our favorite parts of the community. Our staff has long celebrated the green spaces and outdoor activities that make Buckhead such a unique collection of neighborhoods. As the warm weather encourages us to get out and explore with family and friends, we are delighted to share our top 5 favorite places to enjoy springtime in Buckhead.

Bobby Jones Golf Course has been a Buckhead staple since 1932. The course features two 9-hole courses, each with multiple tees and double greens. The different tee and pin combinations provide golfers a unique experience each time they play.

The Murray Golf House at Bobby Jones Golf Course is more than just a clubhouse. It is home to the Ed Hoard Golf Shop, Boone’s Restaurant, and the Georgia Golf Hall of Fame. Don’t miss the state-of-the-art Grand Slam Golf Academy to take your game to the next level!

Atlanta Memorial Park has a lot to offer non-golfers as well. The Bitsy Grant Tennis Center boasts the largest grass-roots tennis organization in the country. Atlanta Memorial Park winds along the southern bank of Peachtree Creek on the west side of Northside Drive. You’ll find lots of picnic tables near the large playground, and plenty of room to play and explore along the creek.

The Northwest Beltline Connector trail connects Atlanta Memorial Park to Tanyard Creek Park and Ardmore Park, where it intersects with the Atlanta Beltline Trail.

The East Palisades section of the Chattahoochee River National Recreation Area provides Buckhead residents with a truly unique hiking experience without driving out of town. The Indian Trail parking lot is just 15 minutes from the Buckhead Village District!

The East Palisades includes more than 10 miles of hiking trails along the bluffs and shoals on the Chattahoochee River. Highlights of the trail system include an overlook deck with panoramic views of the river, and ruins of riverside settlements. If you take the trail far enough north along the river you will find the famous bamboo forest.

The trails along the river are generally easy, but you will find some fairly strenuous climbs between the river’s edge and the top of the bluffs. The Indian Creek parking lot is at the top of the bluffs, so you will be working your way down to the river from there.

The Whitewater Creek parking lot is on the river. You can go on short hikes along the river from here without much climbing, but you can also access the entire trail system if you like. The Indian Creek parking lot can get crazy on warm weekend days, so keep the White Water Creek parking lot in mind as an alternate.

Chastain Park is a 260+ acre park with something for everyone. The walking trails around the park include a 3.4 mile loop and a 2.7 mile loop, and they are usually busy with locals exercising, chatting, and enjoying the neighborhood. The trails and the Chastain Park playground are just the beginning of the activities at the park.

Northside Youth Organization (NYO) operates basketball, baseball, softball, and football leagues at the park. The Chastain Park Tennis Center offers individual and league play. The North Fulton Golf Course is a public course that occupies much of the park. Chastain Arts Center provides classes, summer camps, and gallery space to Buckhead’s aspiring artists.

Chastain Horse Park is a unique community resource. The horse park offers horse boarding, riding lessons, and summer camps. Therapeutic riding and Hippotherapy programs provide multiple equine-assisted activities for a variety of physical and speech-pathology therapy.

Spring is the beginning of the concert series at Chastain Park Amphitheater. Music lovers are treated to 40-45 concerts between April and October each year.

PATH400 has quickly become an integral part of Buckhead’s daily life. The path is a great way to get some exercise and explore the community without sitting in traffic. You’ll find lots of art installations along the path, and you will be treated to unique skyline views and serene wooded sections along the way.

The current route of PATH400 begins at Peidmont Rd. and Adina Dr. at the south end, and follows GA400 to Wieuca Rd. The southern end includes an easy connection to the South Fork Trail at the Confluence Bridge, and a future connection to the Atlanta Beltline at Piedmont Rd. The next phase of the Path will continue north from Wieuca to Mountain Way Common, and then continue north to meet the Sandy Springs path system.

The newest section of PATH400 stretches from Miami Circle to the Gordon Bynum Pedestrian Bridge at Lenox Square. This section features a large mural by local artist, Jonesy, and a wetland area that is home to wildlife that you would probably not expect to see along GA400! If you haven’t explored PATH400 in a while, you will probably be pleasantly surprised when you get out on the path this spring.

If soaking up the springtime sunshine next to a picturesque duck pond is more your speed, then the Duck Pond is for you. This serene 7.5 acre park is nestled within the Peachtree Heights East neighborhood, just a few blocks from Peachtree Road. Bring a picnic lunch and some good friends for the best results.

The pond is definitely the main attraction of the park. The park is named for the distinct Muscovy Ducks who inhabit the pond, and you will find Canadian geese and other visiting ducks depending on what time of year you visit. Look for turtles sunning themselves on sunny days as well. The meandering path around the pond provides a nice walk, as well as access to the numerous fields that are perfect for picnicking. The flock of ducks that lives in the park has seen reduced numbers over the past few years. A few concerned residents informed us that visitors feeding the ducks inappropriate food (like bread) has been detrimental to the flock. Peachtree Heights East residents are happy that visitors love their little park, but they ask that you respect the rules when you visit. That means no fishing, no grilling, and please don’t feed the ducks.

Nearly eight years have passed since an incurable killer of a beloved garden plant was first found in Georgia, lurking in a Buckhead lawn. Now boxwood blight has spread to devastate historic gardens and local landscapes across the country, while science is starting to catch up to the tricks of the fungal infection behind it.

Chris Hastings, owner of the Chamblee-based tree care firm Arbormedics, has been battling the blight in Buckhead gardens from Day One. He summed up the current state of affairs: “Is it bad? Yes. Has it gotten worse? Yes. Is it now commonplace on almost every street in Buckhead? Yes.”

However, Hastings adds, it also has not wiped out the plants as was originally feared. “But over all that time… it comes in waves,” he says, noting a particular blight-battling hint in its link to rainfall and moisture. “And really we’re still trying to figure out, what are those key moments? Because it’s not always as clear as you would expect.”

“The boxwood is such a beloved plant. It’s the aristocrat of the Southern garden.”

Chris Hastings, owner, Arbormedics

Jean Williams-Woodward is a University of Georgia Extension plant pathologist who was on the team that first identified the blight on boxwoods on that Buckhead property back in 2014. She says that “we’re still finding out things about this disease.”

The future she sees taking shape — much like the famously sculpture-friendly boxwood itself — is one where improved practices, disease-resistant breeds and a shift to other types of landscape plants will contain the blight.

Boxwood (Buxus sempervirens) is a type of small-leafed, evergreen plant native to Asia that for centuries has been popular nearly worldwide as an ornamental. In tree form, it makes for stately, pillar-like entrance ornaments. It also takes well to being shaped with trimmers and is hugely popular for rectangular hedges — which is how the plant got the “box” name. The English and American varieties are wildly popular cornerstones of the traditional Southern aristocratic garden.

“In the South… it’s a plant that tugs on your heart,” says Williams-Woodward. And on your purse-strings, too — for nurseries and landscapers, “It’s a huge economic impact.”

“The boxwood is such a beloved plant. It’s the aristocrat of the Southern garden,” said Hastings, adding that’s why homeowners are willing to battle the blight instead of just getting replacement plants. “It’s been used for hundreds of years here. It’s been tied in people’s minds and their sensibilities to what a gorgeous Southern garden looks like. So it’s very hard to contemplate having a holly instead.”

This pretty picture started going bad with the original discovery of boxwood blight in the United Kingdom in the 1990s. An American infection was just a matter of time, and in 2011, the first U.S. cases were found in Connecticut and North Carolina nurseries. A Virginia nursery was the likely source of infected plants that led to that first known Georgia case in Buckhead in July 2014, on a private property that the experts won’t publicly identify for privacy reasons. The blight may well have been elsewhere in Georgia already.

The blight has continued to spread around the country and has become a major pest in historic gardens. Colonial Williamsburg, the famous historic area in Virginia, has been battling the blight for over five years in its collection of more than 8,000 boxwoods, many dating back a century or more, according to media reports. In the past year, major boxwood culling was carried out at the historic homes of poet and author Carl Sandburg in North Carolina and 19th-century politician Henry Clay in Kentucky.

“I’ve seen very historic gardens where every single plant has been lost… They just look like bare stems,” said Williams-Woodward.

The blight is a species from a genus of plant-infecting fungi. It kills boxwoods by causing their leaves to die, and can infect the stems as well. The blight can also infect other plants in the same family, including pachysandra and sweet box, according to Williams-Woodward, but is often not so lethal to those species. Some varieties of boxwoods have a degree of resistance, but the beloved dwarf English and American cultivars are not among them.

The fungus spreads by sticky spores that spew off the plant into the environment. Once it infects a plant, there is no known cure.

Williams-Woodward says the fungus has probably been around for hundreds of years, but was less prone to kill boxwoods in their original native areas of today’s Asia and Turkey, where the climate is drier. Wetter conditions are among the factors that make the fungus thrive.

In the first decade of battling the U.S. blight, tactics have shifted along with research and field practice, and even now there is some disagreement among experts about how the fungus spreads and should be fought.

Hastings notes that the early U.S. discoveries were inside mid-Atlantic nurseries and greenhouses, with plants packed closely together. That led to some assumptions about how transmissible the fungus was and that the air might be a major transmission method for its spores.

“So I do think there was a little bit of a misunderstanding in the early days about how contagious it, how lethal it is,” said Hastings. “So a lot of the original reports that came out and still linger were like, ‘If you have boxwood blight on your property, tear them all up and run screaming for the hills.'”

Yet today, he says, some original boxwoods continue to survive on the original Buckhead property that was the first known to have the blight. He said a second Buckhead property where the blight was found in backyard plants at virtually the same time still has boxwoods, too, including some within 100 feet of those with the outbreak.

What everyone agrees on at the moment is that moisture is key to the blight’s spread and that the disease can be managed with multi-pronged tactics. The situation can be illustrated with imperfect analogies to more familiar human diseases. Think of the blight as a lethal version of athlete’s foot that, like that fungus, infects and spreads explosively in wet environments. And like the coronavirus behind COVID-19, experts can’t currently cure or eliminate the blight, but can contain and manage the disease through a combination of treatment, built-up resistances, avoidance and new, safer cultural practices.

The blight erupts when the weather is wet and temperatures are moderate, said Williams-Woodward. The symptoms may retreat in hotter and drier months, she said, giving plant-owners a false sense of relief while the incurable infection remains.

Water is also now believed to be one major way the fungus spreads, as splash-back from rain or irrigation droplets hits other nearby plants. “Spores produced [by the fungus] are very sticky and they cluster together,” said Williams-Woodward. “So this pathogen or disease is not something that blows around in the wind. It’s mostly water-splashed.”

Hastings agrees that water is a major factor, saying that the earlier wind-spreading explanation never matched what he saw in the field. “We do not see it marching through a garden,” he said, explaining that the blight is almost always paired with heavy moisture from the environment. He said he often finds it tied to a broken rain gutter or — especially in lawns of well-to-do Buckhead homeowners — irrigation systems that are overused when rainfall is perfectly adequate.

“Irrigation, irrigation, irrigation is the number one reason that people have [boxwood blight] problems in Buckhead,” he said. He won’t even take on a boxwood client who won’t properly manage an irrigation system.

“I think we will end up in some kind of combination of planting less-susceptible varieties, plus some cultural practices … So we can manage this disease.”

Jean Williams-Woodward, University of Georgia Extension plant pathologist

Research shows that animals and humans may also be carriers of the spores, says Williams-Woodward. Boxwoods “actually smell like cat pee,” she said, and so may attract cats and dogs to mark them, resulting in spores getting on their fur to be spread to other plants. She said she saw one garden where boxwoods were blighted at the same level as the cushion on a patio chair that a cat slept on. Squirrels, rabbits and turkeys are other suspected spreaders.

Landscape workers may also spread the spores on their hands and equipment, Williams-Woodward said. She is currently conducting experiments on easy ways for landscapers to disinfect their gear before traveling to another property. Regular Lysol spray is looking highly effective, she said.

Hastings doesn’t buy it. He says animals and humans pale in comparison to water and another form of Buckhead lawn epidemic — the use of high-powered leaf-blowers that could blast spores all over surrounding properties. “I don’t think we need to be caging our cats and spraying down our landscapers,” he said.

What about spraying the plants themselves? After all, you can knock out athlete’s foot pretty fast with a can of fungicide from the drug store. Turns out it’s not that simple for boxwood blight, and Hastings and Williams-Woodward agree it’s no main solution.

There are fungicide sprays that can effectively reduce blight symptoms in a plant, said Williams-Woodward. But it requires regularly repeated application that few landscapers or arborists will perform, and that can be cost-prohibitive and raises issues of environmental pollution. Overuse of the sprays also could lead to the evolution of fungicide-resistance strains of the blight, she said.

Hastings said he’s one of the few local arborists who will spray for boxwood blight, but only as part of an integrated approach, as he also has environmental and best-practices concerns.

“Do we put every boxwood in town on a chemical crutch? Absolutely not,” he said, again emphasizing moisture as the main problem. “The key to getting ahead of this is thinking about your basement getting mold or mildew… You don’t run in there and start spraying Clorox everywhere. … You get rid of the water source.”

Another option is blight-resistant varieties of boxwood. Some already exist and others are being cultivated. But a note of caution on some of those, such as Japanese and Korean varieties: Williams-Woodward said they may be less able to catch and die from the blight, but can still carry and spread it, making them “sort of a Trojan horse.”

Her preferred tactic is to simply replace smaller boxwoods with a totally different species, like Japanese holly, and to prune the lower branches of larger ones to avoid the water-splash effect that may spread the spores.

Hastings says he’s hopeful the boxwood blight battle eventually will take a similar course as brown patch, a different fungal infection that affects fescue grass lawns. He said that landscaping veterans have told him about the brown patch plague in the 1980s, which coincided with a boom in lawn irrigation systems. Initially, he says, there was similar advice to landscapers about attempting to disinfect mower blades and the like. Today, he said, brown patch is manageable in a coordinated program of lawn management techniques that continues to allow fescue to be planted.

Williams-Woodward also looks to a future of containment and management. She said research continues on exactly how the blight spreads, the environmental conditions that favor it, how its biology works, and arborist techniques. “I think we will end up in some kind of combination of planting less-susceptible varieties, plus some cultural practices … So we can manage this disease,” she said.

For more details about boxwood blight, see the websites of the UGA Extension and the Georgia Department of Agriculture.

A rebuilt fire station and a Chastain Park parking deck are among the western Buckhead items that could be funded in a $700 million from an infrastructure bond and transportation sales tax the City hopes to put on the May 2022 ballot.

The projects were part of a list, not set in stone, of potential Northwest Atlanta improvements presented at a Nov. 22 virtual meeting about the funding plan. Projects for Northeast Atlanta, including eastern Buckhead, were discussed at a similar Nov. 18 meeting.

Atlanta is in year five of an existing transportation special local option sales tax (TSPLOST) and the Renew Atlanta infrastructure bond program. Both sources have been used to execute a wide variety of projects, from street improvements to public art. They also have been controversial for slow pace and confusing, changing project lists.

The City aims to essentially extend those programs with a $400 million infrastructure bond and a 0.4% TSPLOST estimated to be worth $300 million. The City wants to put both questions on the spring 2022 primary election ballot, which likely will be held in May, officials say.

To do that, City officials need approval of the City Council, which they hope to get Dec. 6 following Dec. 1 hearings before the Finance/Executive and Transportation committees.

A reconstruction of Fire Station 26 at 2970 Howell Mill Road is on the project list. The station was renovated last year, but like virtually all fire facilities is considered subpar for modern use.

Among many other projects are a path on Northside Parkway that would connect to North Atlanta High School, and resurfacing of such streets as Blackland, Mount Paran and West Paces Ferry roads.

For Northwest Atlanta overall, the project list features 21 or 22 transportation projects, includin about 13 miles of sidewalk repairs, 12 miles of new sidewalks, and 16 miles of “major street projects.” The list also includes improvements to 10 parks or recreation facilities.

Of the estimated $700 million, $190.5 million would go to citywide projects. Another $3 million would go to discretionary funds of City Council members to spend locally as they wish.

As at previous meetings, City Deputy Chief Operating Officer LaChandra Butler Burks was asked about how Buckhead cityhood would affect the funding proposal. If the General Assembly approves cityhood legislation, it could be a ballot question in 2022 as well, six months after the bond and TSPLOST vote. Burks repeated her answer that the City is proceeding on the assumption that Buckhead will not secede and keep doing so “unless something very different happens.”

There is no final or permanent project list, said Burks, nor is one needed to get the bond and TSPLOST questions on the ballot. However, she said, City officials intend to have a project list, with a cost estimate for each, to present to the council as it considers whether to proceed on the ballot question. She acknowledged that cost estimates were a problem in the last round of funding, requiring the creation of a new list, but that the City believes its current numbers are accurate.

The public appears to have little influence over the lists at this point, with the meetings functioning primarily as advertising to promote the effort to get the funding questions on the ballot. The Nov. 22 meeting, like others in the series, had a brief question-and-answer period, but no opportunity to directly change the project list or create a new one. Burks said the PowerPoint-style presentations from the meetings will be posted online somewhere, but indicated that recordings of the meetings will not be.

A two-month “test” period of sharing the golf course—one day a week—with walkers, bicyclists, picnickers, and everyone else is underway

Since the coronavirus pandemic clamped down upon Buckhead in March, District 8 Atlanta City Councilmember J.P. Matzigkeit has participated in panel discussions, countless conversations in public, and no shortage of personal introspection about the future of Chastain Park. Our story and photos on the issue in early May generated a massive response, showing passion on all sides of the debate. The public input has partially paid off, with the Atlanta Parks Department agreeing to keep the golf course closed to allow public use of the greenspace on Tuesdays for a 60-day period.

Matzigkeit’s district covers the park and golf course. He lives a stone’s throw from it. And years ago he cofounded the Chastain Park Conservancy and helped craft the park’s masterplan. Yet he’s heard the pleas that call for ditching golf at the park—Atlanta’s largest at 268 acres, with the vast majority reserved for golfing—altogether, or at least reducing the course to nine holes. And like many, as ironic as it might sound, he speaks of the early days of the pandemic as a halcyon time, in terms of the park’s communal spirit, when the grassroots idea to “Free Chastain Park” of golf gained traction.

Over 1000 people have voted in the Buckhead.com poll since it was published in early May. As of press time, 56% of voters wanted to see change, and their wish has been partially granted…for now.

“It was incredible, it really was,” said Matzigkeit. “During COVID, with the complete shutdown, you had a need for people to be outside, to exercise and enjoy the fresh air in a physically distant way. The golf course gave them that escape, and they discovered how fabulous the course really is.”

After three months, however, Chastain Park’s public-access free-for-all ended last week—Tuesdays notwithstanding. And now, impassioned public opinion about the park’s accessibility is once again running the spectrum.

Chastain’s historic North Fulton Golf Course reopened to golfers June 15 (or at least to players who hold fore and annual passes) with safety measures that include keeping the clubhouse closed and allowing just one golfer per cart. Public access, meanwhile, has been relegated to park hours (6 a.m. to dark) on Tuesdays only, for a 60-day period that Matzigkeit calls “a test.”

“It’s a golf course, and if we can use it responsibly, that’ll be a data point, and if we can’t, that’ll be another data point,” he said.

After the city decided in March to shutter golfing operations and open the fairways like any other public park, Atlanta’s Department of Parks and Recreation conducted an analysis that included golf course usage data at Chastain and the schedules of other city-operated courses, before deciding on Tuesdays for public access. Between now and mid-August, meetings for public input are expected, and any decision to continue golf-course closures or not will come from the city’s parks leaders, Matzigkeit said. The Chastain Park Conservancy’s executive director, Rosa McHugh, said the new protocol “looks like it’s working very well,” in an email. But, she added, “it’s only been a week, so it’s hard to tell long-term.”

Matzigkeit isn’t aware of another course in metro Atlanta that allows public patronage, but one famous example, he noted, is St. Andrews in Scotland, which has been converted to a community greenspace most Sundays for hundreds of years. “If you can do it in the birthplace of golf,” Matzigkeit said, “we can do it here in Atlanta, Georgia.”

A visit to the park Tuesday evening showed a different, quieter scene than weeknights in the more socially restricted months of March, April, and May.

Sweltering weather at 5:30 p.m., the onset of vacation season, and the resumption of some youth sports were likely all factors, but recreationists were sparse across the links. A few guys did wind-sprints up a steep hill, and an eclectic mix of walkers—from teens in workout gear to masked elderly folks—hustled along cart paths. Probably twice as many people were seen on the PATH Foundation trail around the park, walking dogs and jogging along the periphery.

One issue, as Buckhead resident Rebecca Peckham pointed out, is that visitors not privy to the community’s Nextdoor site have seen golfers back on the course and assume it’s closed. She’s all for keeping it that way, too, throughout the week.

“My big concern is a slippery slope,” said Peckham. “You go to Tuesday (for public access), and that becomes Tuesday and Wednesday, and people say, ‘Isn’t this great, let’s do more days, and the golfers don’t really need it, except for the weekends.’ Then it becomes, ‘Why don’t we do Music Midtown in Buckhead!’ I mean, that’s probably a little extreme, but it’s the City of Atlanta, all their property, so you don’t know.”

Conversely, another walker and longtime nearby resident, Donna Hinkes, wants to see the park accessible as many days as possible.

“When I first moved to Atlanta, people said, ‘Oh, you’re so lucky, you’re going to live by Chastain Park.’ I said, ‘Chastain Park? It’s a golf course with a sidewalk around it,’” said Hinkes. “Then, during the shutdown, there were people having picnics, children learning to ride their bikes, people playing croquet in the grassy areas… We want the golfers to be able to golf, but it’d be nice to have a Sunday, or even just a Saturday and Sunday evening, so you can come with your family.”

The only downside to so much access, Hinkes said, was the occasional rule-breaker who didn’t leash large dogs or left garbage behind. That latter issue swayed Chastain Park resident Britton McLeod from being a staunch supporter of fully opening the park to a borderline naysayer.

“Closing the park and opening it only on Tuesdays is actually a good thing,” said McLeod. “It got kind of out of hand. Teenagers, mainly, and preteens were not respecting the rules. There was a lot of pollution in the park and also in connecting neighbors’ yards where kids walk. It really became an issue for the neighbors.”

Allison Vuicich, who lives across the street, applauded any public access she can get, but worried aloud: “I don’t know how it’s going to work with (the city) losing the money, because from what I understand, this helps fund the other golf courses of Atlanta.”

That’s true, and Chastain’s course is one of—if not the most popular courses in Georgia, according to Matzigkeit, with an estimated pre-coronavirus patronage of 50,000 rounds annually. Data for the 2019 calendar year, as provided to Buckhead.com by the city, show Chastain’s golf course raked in more than $1.6 million from 56,200 rounds played, with the monthly highpoint being 7,079 rounds (July) and the low 1,647 (January).

Designed by H. Chandler Egan, a colleague of Bobby Jones who also helped design Pebble Beach in California, the course opened in 1937 and remains the only city-operated option for golfers north of Candler Park. Rates top out at $25, including carts, with weekday early-bird specials of $10 rounds. “There’s also some history here in terms of Black Atlantans playing this course in a time of segregation,” Matzigkeit, who’s not a golfer, pointed out. “It’s a wonderful course, with a lot of history.”

Tuesday’s tour ended back near the clubhouse, where James Hancock, who lives near Buckhead Village, was lounging sweaty in the shade, on the putting greens. He reflected on his very first visit to the park that evening, a failed attempt to walk the entire course with his pals.

“It’s a great view of the city, and the trees, and the forest,” said Hancock. “I see myself coming back, absolutely. Maybe I’ll walk the whole thing next time.”

Omar Toledo, a stock trader who lives in Atlantic Station, boarded a six-wheel, electric-powered contraption called a summerboard in the middle of Chastain Park Golf Course’s sloped first hole on Tuesday. It was 83 degrees and sunny at 5 p.m., the glassy high-rises of Buckhead shining beyond the trees. The only rush-hour traffic in the area was found along the northern edges of the park, where patrons jockeyed for parking spaces. Everyone seemed to carefully keep their distance from strangers, which wasn’t difficult, given the enormity of space afforded by a golf course without golfers. Toledo’s friends had tipped him off that Chastain Park, in a time of novel coronavirus restrictions, has been like Piedmont Park, minus the crowds. “It feels good—definitely worth the trip,” he said, before cruising off toward Hole 2, as if snowboarding on a cart path.

The global pandemic has transformed Chastain Park’s rolling fairways, waterways, and greens into what’s unequivocally one of the more gorgeous, versatile, and massive public green spaces in Atlanta—at least for now. Wandering the course today, you see Atlantans of all ages involved in every manner of outdoor activity not involving clubs and golf carts. In interviews, many echoed what’s become an impassioned if still grassroots idea: permanently converting the course into a public park (a “Free Chastain Park” sentiment, if you will); or at least reducing it to a nine-hole course so more acreage is accessible to nongolfers, as with the recent retooling of Bobby Jones Golf Course, now operated by an outside foundation. City and park officials are hardly calling the idea quixotic or impractical, though it’s too early to talk potential funding and other logistics. Another contingent of locals, however, is eager to have its historic and popular golf course back, even if they don’t play.

“This is spectacular, walking on the greens and the cart path,” said Buckhead resident Nancy Cowles, gesturing across the hills. “There’s all different ways to go—loop around here, over there.”

Her husband isn’t so sure.

“My thought is, it’s great for now, but it needs to stay a golf course,” said barefooted Brooks Cowles, walking their dog, Lucy, on the soft Bermuda. “There’s a lot of people who can’t join private clubs around here. It’s hard to get in. A lot of golfers rely on this as a public course.”

Converting the golf course wouldn’t be without local precedent. Piedmont Park, which has drawn national criticism for its social-distancing-averse crowds this month, featured a nine-hole course along 10th Street (with part of today’s Park Tavern serving as the clubhouse) until it closed in 1979 for more public parkland.

Today, Chastain’s 268 acres make it Atlanta’s largest city park—more than double the size of Grant Park (the city’s oldest) and 100 acres bigger than Piedmont. But the vast majority is reserved for golfers under normal circumstances. The holes are ringed by a walking path used by an estimated 500,000 people annually, which is the amenity that drew heat for being crowded in the early days of shelter-in-place, before the residents of Chastain Park took over the golf course for picnicking, Frisbee-tossing, and anything else within reason.

The golf course, which dates to 1937, was designed by H. Chandler Egan, a colleague of Bobby Jones who also helped craft Pebble Beach in California. It’s the only city-operated golf course north of Candler Park, with rates topping out at $25, including carts, and weekday early-bird specials of $10 rounds. City officials consider it Atlanta’s top public course. But the district’s city council representative—J.P. Matzigkeit, who cofounded the Chastain Park Conservancy and helped create the park’s 2008 masterplan—said he’s open to exploring “whether we could share” and have “a historic golf course and a public green space” together. The golf course, as Matzigkeit pointed out, is said to be Georgia’s busiest, with revenue that supports other courses across the city.

“Every time I walk around the park, people share their thoughts about the golf course with me,” Matzigkeit wrote in an email to Buckhead.com. “People are passionate about both keeping the golf course exactly as it is, as well as turning the golf course into green space. I represent both groups of people.”

The Chastain Park Conservancy’s executive director, Rosa McHugh, declined an interview but supplied a statement that reads, in part, that her organization “believes the community deserves the opportunity to discuss [a new park] concept. However, we stress the importance of having all the facts on the table… [W]e would like to encourage the discussion to explore creative shared public uses and opportunities for activating acres of underutilized parkland for passive recreation.”

Since COVID-19 upended everyday life in America, that recreation at Chastain has included sunbathing in sand traps, caravans of families on bikes, kids playing lacrosse and riding scooters, yoga and dancing classes, outdoor dining from nearby food trucks, fitness boot camps, swimming in the pond and Nancy Creek, and even teens hosting student council meetings. For nongolfers, it’s a totally new perspective on Chastain, offering what Buckhead Realtor Ben Hirsh called a “lightbulb moment” for the community.

“Buckhead is blessed with so much greenery and tree canopy, but there’s something about a beautiful public park that transcends even a spacious private yard,” said Hirsh. “It’s the prettiest park in Atlanta, and because I’m not a golfer, I was not aware of that until now. If this becomes permanent, I could see a possible increase in property values for the Chastain Park neighborhood as a result.”

Elsewhere on the park tour, frequent patrons Will Luckey and his son Tristan were walking their Shih Tzu, Dipper, around the pond. “It’s never been like this,” said the elder Luckey. “It’s beautiful, a great place to be able to come, with all this going on.

“To share the openness of it [permanently] wouldn’t be too bad,” he continued. “Pebble Beach in California, it’s a public facility. You can be playing there, and 300 people are walking around watching you. Maybe [having parkland] around the perimeter’s and stuff, that’d be cool.”

On a course bridge, a couple who requested anonymity were enthralled with watching a water snake ambush minnows. They live a block away and have used the newly accessible spaces every day since March. Running on grass, the wife said, has proven healthier for her.

“For all these kids, it’s unstructured, free play, and they’re using their imaginations,” she said. “We’ve had such a beautiful spring this year, and this space was perfect, but I wondered what happens when it’s July and 90 [degrees]? Will people still come out? Well, they still go to Piedmont Park.”

Her husband added: “It’s been incredible, and there’s two thoughts on it: Most people love it, but they’re weary of it becoming permanent and that there will be, you know, bad elements coming in. That was like the big thrust of everybody’s thought process.”

Her: “I have heard on Nextdoor Chastain complaints about trash. Where? I’ve found an earring and an ear pod, that’s all… It’s so clean that I would notice that.”

Him: “Will [the park expansion idea] gain traction? I don’t know. There are some big hitters over here who can make stuff happen, you know.”

Her: “I wonder which side they’re on? Probably the big-hitters aren’t golfing here.”

In the short term, exactly how long Chastain frolickers will replace golfers isn’t clear. Matzigkeit said an advisory panel established by the mayor’s office is expected to report findings and bring recommendations to the council about how and when to open city park operations by May 15. The council, for now, is in wait-and-see mode, he said.

Whatever happens, Britton McLeod, who’s lived around the corner from Chastain Park for seven years, will look back fondly on one aspect of the pandemic malaise.

“We’ve always loved this area, always thought it was special, but now we feel the neighborhood can truly come together,” said McLeod. “It’s like having Piedmont Park in north Buckhead, and that’s very unique to the city. I really feel like it’s brought our community together in a healthy way.”

Concerns about street name confusion causing delays for emergency response to locations in Chastain Park has led to a proposed name change of West Wieuca Road, the thoroughfare that cuts through Chastain Park. On May 6, the Atlanta City Council voted to rename the road, likely to Chastain Park Avenue NW.

The office of City Councilmember J.P. Matzigkeit reported that there were at least 3 instances of misdirected emergency services to the Chastain Park pool in 2018, as responders mixed up the similarly named West Wieuca Road NW with West Wieuca Road NE.

The affected stretch runs from Lake Forrest Drive and Powers Ferry Road, shown in red in the above Google Map. This proposed name change would affect the Galloway School and the Chastain Park Arts Center, both of which are located along this strip. The measure is currently awaiting action by Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms.

On the evening of Friday, January 4, neighbors began to notice a glow in the center of Chastain Park. The fire department was notified and before long firefighters were on site battling the blaze that ripped through the Chastain Park Conservancy’s main office, an old Quonset hut that had served as their headquarters since the non-profit was founded in 2003. The fire was eventually put out, but not before demolishing the structure and everything within.Fortunately, the resident goat Chuck, barn cat Johnson, and the chickens and honeybees were all unscathed, and due to the time of day the building was unoccupied.

As the flames were put out the full scale of the damage could be easily seen. The hut, originally built in 1949, was used as a headquarters for much of the build out of Chastain Park as we know it today. Eventually the hut was abandoned and forgotten in a thicket of trees until about 15 years ago when a volunteer discovered the structure. In the years since, the building has housed gear, offices, and provided a meeting place for volunteers and community members.

Chastain Park Conservancy’s co-founder, the late Ray Mock, was a beloved figure in the community. He lived for the park and was devoted to its upkeep and care, treating the barn as his second home. Within those walls, Mock spent countless hours organizing volunteers and scheduling events to benefit Chastain Park. His tireless historical research led to many discoveries, such as the instance when he identified unmarked graves in an underused part of the park which garnered quite a bit of discussion and attention from the media. In fact, the Conservancy was in the process of renaming the barn and the area as “The Ray Mock Memorial Green” in his honor, and renovations were underway to fix up the building to better suit the Conservancy’s needs.

And just like that, in one evening, it was all reduced to rubble. Chastain Park Conservancy Executive Director Rosa McHugh addressed the event on their website, stating that while devastating, the fire was not about to slow down the Conservancy’s efforts to “restore, enhance, maintain and preserve” the park, per the organization’s mission.

On Tuesday, January 8 McHugh launched a gofundme to help raise funds to rebuild the facility, and as of the following morning the campaign had raised nearly $10,000 of their $50,000 goal. Neighbors, community members, and lovers of Chastain Park have been quick to offer their financial aid to the non-profit in this time of need.

“Like Atlanta’s beloved symbol, the Phoenix, the Conservancy will rise again – better than ever – from the ashes,” wrote McHugh. “Our board, supporters, volunteers, the city and park patrons will see to that.”

Those interested in contributing can visit their gofundme campaign here.